Finding Heart in the Absurd

In the wild, neon jungle of Kamurocho, I once found myself teaching a shy dominatrix how to project confidence. Moments later, I was chasing a thief who stole a child’s video game, only to learn that the so called “thief” was a desperate father trying to reconnect with his son. Such is the world of Yakuza sidequests, always absurd, hilarious, and surprisingly heartfelt. These substories break up a crime drama with bursts of silliness and sentimentality, achieving a balance many games struggle with. Indeed, the Yakuza series is famous for juxtaposing gritty main plots with absurd side tales that carry genuine emotional weight. One moment Kiryu Kazuma is fending off gangsters, and the next, the dude’s helping a stranger find love or dignity in the unlikeliest of scenarios. This sharp contrast really does tap into something special. By disarming us with humour, these sidequests open up pathways to empathy and human connection that can feel even more resonant than the main story’s high-stakes heroics. In Kamurocho’s side streets, absurdity becomes a gateway to vulnerability. We laugh at the ridiculous setup, will let our guard down, and in that wake, a genuine bond forms between player and character, hero and NPC. The result is some kind of emotional alchemy, through laughter, a feeling of warmth and connection emerges, turning brief encounters into memorable human moments.

Humour as a Pathway to the Heart

Humour has a disarming power, as it replaces stress or anger with a moment of joy, surprise or connection, which dissolves any distressing emotions. In a tense game, some fucking wild side quest can feel like a lungful of fresh air, and a chance to laugh when you might’ve wanted to cry. It’s no wonder that players often recall sidequests as their most heartfelt experiences in this series, because humour has primed them to be receptive. When we laugh, our brains release endorphins and we bond, even if that bond is with a fictional character. Yakuza’s writers seem keenly aware of this, because the humour in its substories is rooted in character, and not just randomness, which means we aren’t laughing at NPCs so much as laughing with them in their predicaments, and that distinction is key here. The affiliative humour, the inclusive, empathetic comedy; turns these bizarre scenarios into shared experiences between player and game characters. We become complicit in the joke. For example, when Kiryu helps an eccentric man in a diaper who leads a secret baby roleplay club (Shoutout to the Gondawara Family!), the situation is outrageous and provokes nervous laughter. But Kiryu’s earnest, respectful handling of it (barely batting an eye at the absurd request to spoon-feed a grown man) invites us to see the humanity in the funny. We end up feeling for this strange dude rather than dismissing him, because a inexplicable, absurd event can initially threaten our sense of how the world works, but if we recognise it as play, basically if we ‘get’ the joke, it no longer provokes anxiety. Instead, we engage with it openly. In Yakuza, we expect absurdity as part of the world’s fabric, so we embrace each weird substory rather than resisting it. This open-minded engagement is the perfect ground for empathy.

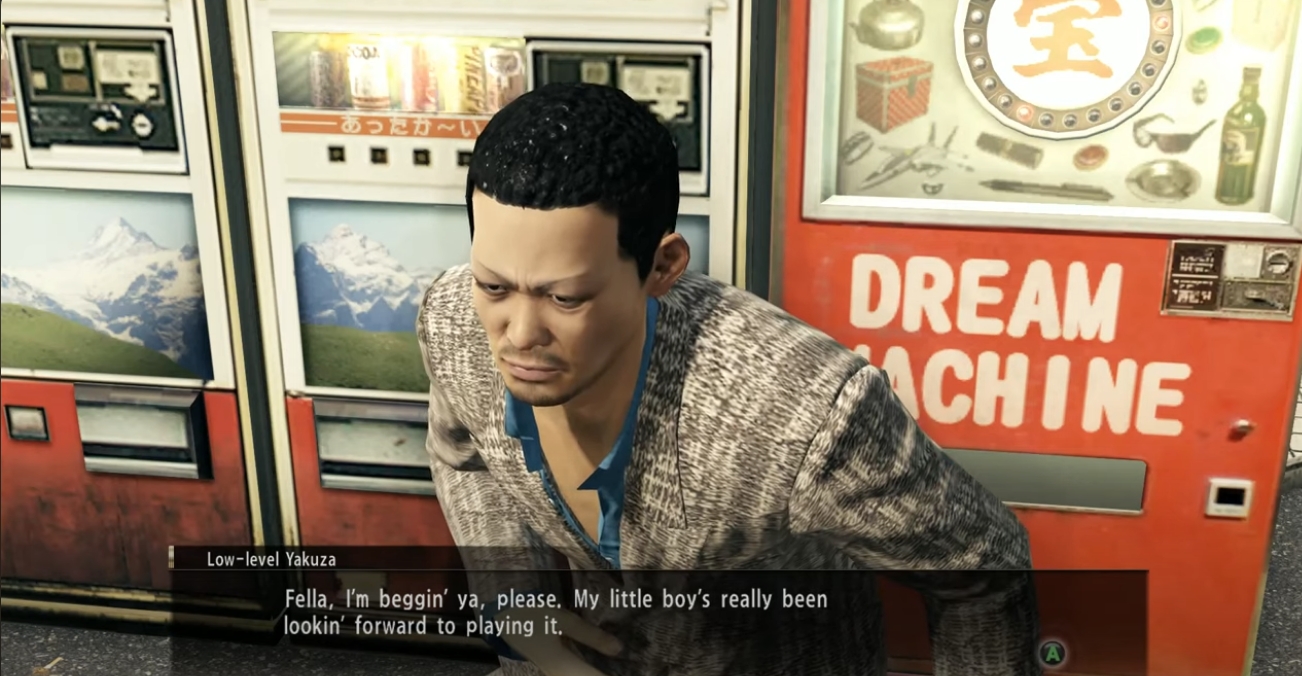

Importantly, humour in these sidequests usually sets up an emotional payoff. After we’ve had a hearty laugh, our defences are down, and we're completely primed for some twist that tugs the heartstrings. Yakuza is a master of this kind of maneuver. Let’s talk about another one, in the substory of the stolen video game, the quest escalates from a fun 1980s nostalgia trip to a comical chase, and finally to a gut-punch revelation that the thief is the boy’s estranged father. The game he snatched was meant as a gift to reconnect with the son he hasn’t seen who, unknown to him, is the very boy he robbed. It’s this damn cycle of absurd coincidences that suddenly hits you with emotional resonance. Then the father, mortified, realises he’s stooped so low as to steal from his own child, and within the span of minutes, we&ve gone from amusement to genuine sympathy. I went from chuckling at Kiryu’s over-the-top, heroic beatdown of thugs to feeling a lump in my throat when that tough Yakuza dad hung his head in shame and regret. Like my goodness, Yakuza really does like to dig at those emotional strings, always catching players off-guard with heartfelt moments in the midst of the comedic chaos. It’s in these moments, that I often feel more connected to the characters than during the dire, save-the-day narrative of the main storyline. The grand dramas make my pulse race, sure, but the little ridiculous stories is usually where the soul is, baby.

The Grotesque, the Absurd, and the Human

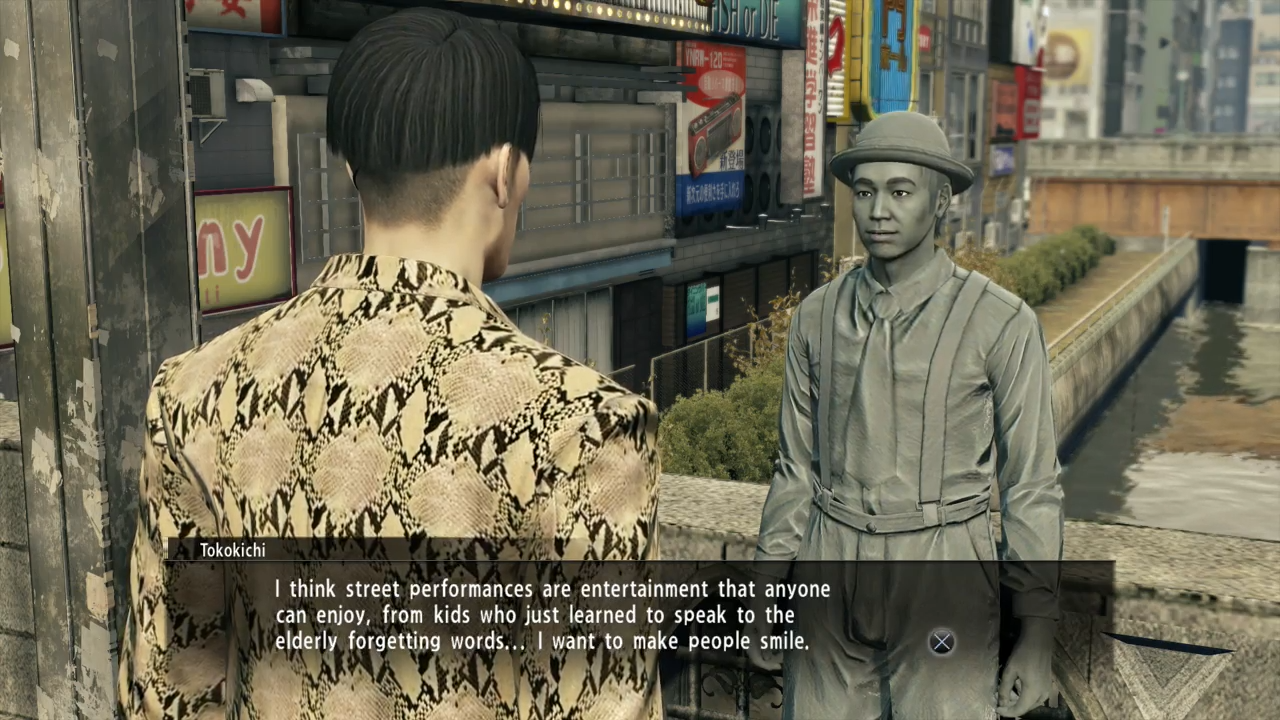

I wonder, why do these ridiculous scenarios evoke such empathy? Well, part of it lies in the grotesque nature of the characters and situations. In fiction, a grotesque character is one who induces both discomfort and empathy. We might cringe a bit or be shocked by their appearance or behaviour, yet we also glimpse their vulnerable, human side. Yakuza’s substories excel at this duality, because they’ll usually introduce us to ostensible weirdos, outcasts, or fools, people we might initially find ridiculous or even off-putting, and then, by the end, they’ve won a piece of our heart. In one case, Majima crosses paths with a flailing street performer painted silver, who’s completely frozen in a mannequin pose. The sight is absurd, the pedestrians mock him, and Majima is just confused. But through the substory we learn the statue man is desperately trying to overcome stage fright and earn a living. Suddenly his trembling in that silver paint draws our compassion. Grotesque characters often have enough good traits that readers find themselves interested nevertheless, and here we are, rooting for a living statue. The initial laugh or shock gives way to understanding.

This pattern hits onto a long cultural tradition, where throughout history, storytellers have always used humour and the grotesque as pathways to truth and empathy. Mikhail Bakhtin’s theory of the carnivalesque in literature, for example, shows how carnival humour with its clowns, fools, and wild scenarios, serves to humanise and unite. In a carnival, the beggar can mock the king; social hierarchies invert, and everyone momentarily stands on equal ground. Laughter creates a great equaliser, setting up an equal status between people. We see bits and pieces of this in those absurd sidequests, where the high and mighty hero is humbled into silly situations, and the lowly NPC is elevated as their companion or teacher for a moment. In Yakuza 0, there’s a memorable substory where Kiryu, a yakuza, ends up coaching a novice tax official on how to pitch a new sales tax to hostile merchants. The idea that a yakuza would help create Japan’s tax policy is so funny and absurd, but in the process Kiryu and this timid bureaucrat form an unlikely friendship. Those kinds of scenes feel like a carnival inversion, where the gangster becomes a public servant, and through that inversion, a human connection is born. We laugh, but we also sense a camaraderie between two people who, in another context, would never meet as equals.

The carnival of sidequests often involves grotesque imagery or scenarios that border on the taboo, but Yakuza doesn’t shy away from the bizarre underbelly of urban life. There are quests featuring adult babies in a secret club, a patriarch in the yakuza who happens to adore playing with toy race cars, and a woman who escapes a brainwashing cult with Kiryu’s help (and that’s after he hilariously mimics the cult’s sacred dance to infiltrate their ranks). These narrative grotesques, function much like the grotesque in art; they’ll jolt us out of complacency and force us to see the person within the caricature. As one art piece by Patricia Piccinini showed a monster cradled like a child, blurring lines between grotesque and tender, the audience’s abrupt reaction turned into an emotion they couldn’t easily pin down, which was basically just empathy in disguise. Similarly, when Yakuza presents a pervert in a trench coat (the infamous “Mr. Libido”) dancing nearly naked on the streets, it’s grotesque toilet humour. But talk to him, and you discover he’s actually lonely and oddly wise in his own way, offering Kiryu advice on the nightlife. The shock and the subsequent understanding combine into a complex feeling of amusement, pity, and respect for an unabashed soul. This blend of disgust and empathy is precisely what defines the grotesque, it piques our interest to see if the character’s better side can prevail over the outrageous exterior; whereas in Yakuza’s case, it usually does. The absurd and even the profane become vessels for emotional truth. A scholar of folklore once noted that what seems absurd or profane to a “closed, ordinary mind” in trickster tales often carries hidden wisdom for those willing to look. Yakuza’s absurd side stories wholly embody this; beneath the comic shine, they almost always have something genuine to say about kindness, resilience, or longing.

Wabi-Sabi and Mono no Aware: Fleeting Beauty in Sidequests

It’s no coincidence that a series like Yakuza infuses poignancy into absurdity. Japan has cultural concepts that cherish the poetic contrast of humour and melancholy, and these shine through in the game’s design. Take mono no aware, often translated as the pathos of things. It’s an appreciation of the beauty in transience, that the gentle, wistful awareness that every moment is fleeting. How does a wild sidequest relate to a zen-like aesthetic of impermanence? Honestly, quite closely. Most substories in Yakuza are usually a one-off encounter, you’ll have Kiryu helping a person, sharing a laugh or a cry, and then they part ways, and life moves on. These encounters are like seasons, they’re unique, brief, and unforgettable because of their brevity. The game encourages us to savour them in the moment, much as mono no aware teaches one to cherish the present knowing it cannot last. More than once, I’ve finished a substory and felt kinda sad realising that this little chapter with that character is over, not wanting it to. There’s this weird sadness in saying goodbye to an NPC I grew fond of in like 15 minutes of playtime. Yakuza doesn’t belabour these partings, but the very structure of its sidequests instills some kind of mono no aware, this gentle sadness that’s tied to acknowledging that the experience will eventually disappear. We’re left with a memory and perhaps a changed heart, much like recalling a brief, meaningful conversation with a stranger years ago.

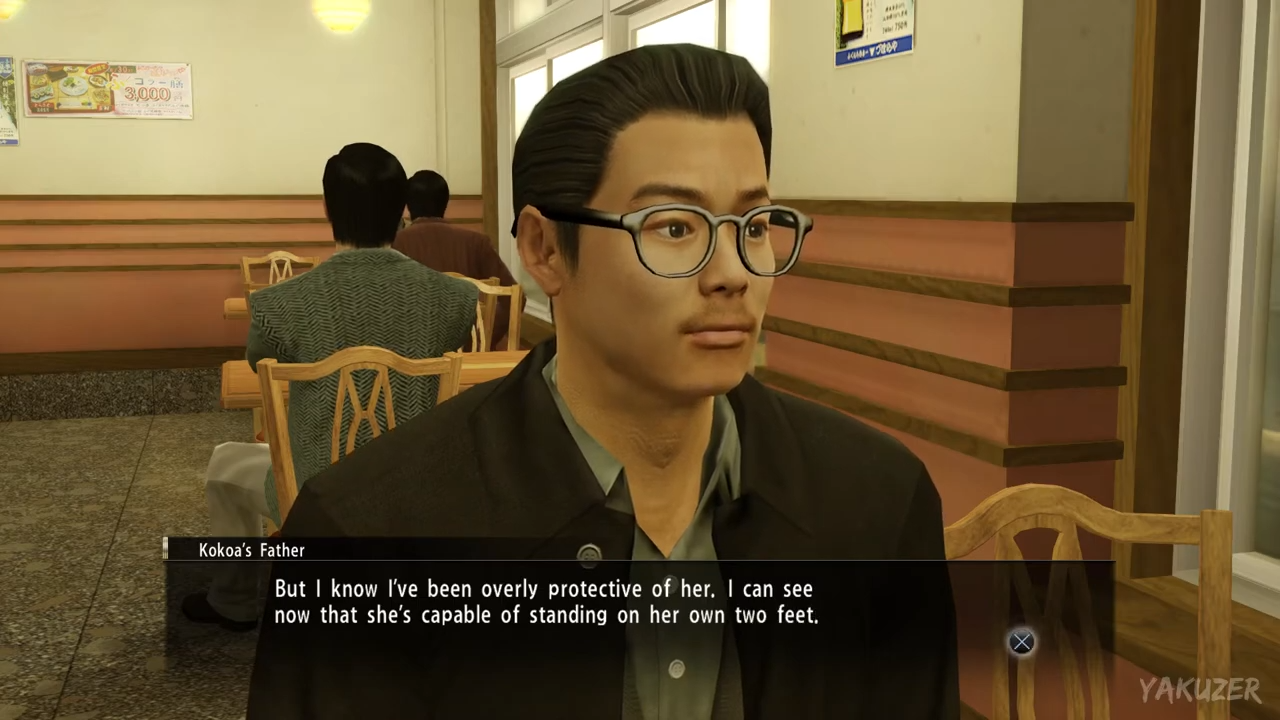

Likewise, the concept of wabi-sabi also is infused in these stories. Wabi-sabi is the Japanese aesthetic that finds beauty in imperfection and the aged. It’s often summarised with three simple truths: “nothing lasts, nothing is finished, and nothing is perfect.” In sidequests, we constantly meet people who are imperfect and in incomplete situations. They’re flawed, weird, sometimes outright broken, like a scam artist who secretly just wants friends, or some aging punk rock singer who fears he’s losing his cool. The beauty of these stories lies in embracing those imperfections. Kiryu never tries to fix these people into some ideal form; he meets them as they are, offers a helping hand or a listening ear, and in doing so highlights their inherent worth. There is wabi-sabi in how a ridiculous scenario can lead to an unexpectedly authentic connection. What comes to mind is the quest where Majima poses as a meek girl’s boyfriend to placate her overbearing father. The dinner is comically awkward (Majima, this imposing yakuza, trying to act like a shy student), and the father sees through it. Yet, by the end, father and daughter come to an understanding, and Majima, the “imperfect” pretend boyfriend, has facilitated a real conclusion. The situation was messy and farcical, but through that imperfection came a moment of genuine familial love. This is the beauty of things imperfect, impermanent and incomplete in action. Sidequests often don’t usually tie things up with a neat bow, they’ll give you just enough resolution to feel rewarding, but leave a bit of life’s imperfections intact. That lingering rough edge actually makes the experience feel truthful and precious. Just as a cracked tea bowl mended with golden lacquer (the art of kintsugi) becomes more beautiful, a story that acknowledges characters’ cracks and quirks can shine brighter than a perfectly polished epic. Yakuza’s absurd substories, in all their fucking wild comical, heartfelt glory, remind us that there is beauty in the flawed and transient nature of human interactions. They embody the sentiment of wabi-sabi, where sincerity and warmth often dwell in the most unassuming, fleeting moments; and those moments matter precisely because they don’t last forever and because no one in them is perfect.

Absurdity as a Social Mirror and Emotional Survival

Beyond personal emotions, absurd sidequests also kinda act as mirrors held up to society, reflecting real social dynamics through a silly lens. The exaggerated scenarios in Yakuza’s urban playground aren’t as far-fetched as they first seem, they’re drawn from the undercurrents of real city life. Tokyo’s nightlife, for example, truly does have its share of bizarre stories and subcultures. But by embedding these into the sidequests, the game is lightheartedly commenting on them. The result is that absurd quests can usually tackle serious themes without the player feeling lectured or depressed. Southern Gothic literature used grotesque characters to spotlight unpleasant social truths without being too literal or moralistic, and Yakuza does the same with their own twist. The cult substory satirizes the rise of shady new-age religions in the 1980s, yet it also empathetically portrays a family nearly torn apart by blind faith. Another quest has Kiryu helping a nightclub owner deal with unruly foreigners, touching on cross-cultural tensions and the Bubble Era’s gaudy club scene, but it’s wrapped in so much outrageous humour and it ends with mutual understanding. In using the absurd to reveal a hidden truth about societal issues, these side stories achieve a narrative subtlety, conveying emotional truths and critiques under the guise of play. You might chuckle at a spoof of a multilevel marketing scam in one quest, but later realise it made you think about why people get suckered in, which is usually loneliness or economic desperation, lending a note of compassion to something often just ridiculed.

Absurd sidequests also resonate because they reflect how people use humour and play as survival mechanisms in real life. In any big city, life can be overwhelming, anonymous, and stressful, and people cope through small moments of levity and connection that seem absurd from the outside. Consider the much recent phenomenon of viral urban pranks, like groups of strangers doing a silly dance in a train station, or people in inflatable dinosaur suits having a picnic in a park. They’re pointless and goofy, yet they forge a brief community and make everyone and the world feel just a bit more alive. Yakuza’s hero, Kiryu, is like an unwitting participant in dozens of such moments. He’s a tough guy and a benignly mischievous force in his city who isn’t above engaging in a toy race car competition with children or playing Santa for a nervous teen. By embracing the city’s absurd side, he becomes a pillar of the community in his own way. This is one of my favourite things about Yakuza, that even in a society bound by strict roles and pressures, the most meaningful human bonds often form in the interstices, the liminal spaces where the rules loosen up. Sociologists and anthropologists observe that in liminal spaces like festivals, nightlife, or even the temporary bubble of two strangers sharing an umbrella in a storm, people actually do drop their social masks and connect more authentically. The sidequest is also a liminal narrative space, where outside the main plot’s duties, the hero steps into a different role, often a goofy or humble one, and meets people as just another person in the crowd. The betwixt and between nature of these encounters is precisely what makes them fertile ground for communion (what Victor Turner called communitas), a direct, egalitarian bond among participants. I’ve felt this communitas in Yakuza’s world when Kiryu and a group of homeless men share a laugh over some pocket change wine, or when he joins a bunch of grown-ups in mascot costumes to perform for kids. These moments, while comical, carry a warmth that mirrors real-life.

Humour, in many cultures, is a balm and a bonding agent during hard times. Studies of disaster survivors and frontline workers find that joking and absurd humour are common coping strategies, and a way to offer breathing room to keep going in hard situations. In Yakuza’s story, Kiryu usually faces intense hardships and violence, but the games allows him (and us) that breathing room. When life feels crushing, a detour into absurdity can be a lifeline. It’s very telling that usually after some of the darkest chapters in the main plot, the games practically invite you to blow off steam with silly side activities, like singing a goofy karaoke song, or helping two complete strangers reconcile over a petty argument. These are the emotional moments of release and restoration, much like how in the real world a group of coworkers might hit a comedy club after a rough week or families might tell gallows jokes during a crisis to stay sane. Humour defuses anger and hostility with communication and perspective, as folklore research notes. In the context of Yakuza, absurd sidequests serve that function, they’ll defuse the darkness and remind us of the fundamental decency still possible in the world. Even Kiryu, a man who has killed and bled, can spend an afternoon helping a child win a stuffed toy. These small acts are like secular prayers for the soul of the city, tiny moments that reaffirm hope and human kindness amid chaos.

It’s also fascinating how cross-cultural this phenomenon is. While Yakuza’s flavour is distinctly Japanese, the idea of absurd humour yielding emotional truth is universal. Folklore everywhere has trickster figures, from West Africa’s Anansi the spider to the North America’s Coyote or Europe’s Loki, who’ll use wit, pranks, and absurd antics to teach lessons or expose vanity. Think of a folktale where the foolish character turns out to be the wisest of all, or where a nonsense riddle contains some actually solid advice. We find a modern version of that in games, the village fool sidequest that imparts the most poignant story of the lot. In The Witcher 3, for instance, a seemingly silly quest about a talking frying pan or a crazy drunken escapade with friends ends up lighting the warmth of camaraderie in Geralt’s otherwise lonely journey. Many Western RPGs have followed suit, creating side missions that start off as farce and end with you wiping a unexpected tear. Fallout uses absurdity to highlight humanity, I remember that cult of undying ghouls building a rocket (which is ultimately a wacky endeavour that ends as a tale of hope and delusion in equal measure). In Disco Elysium, the most empathetic insights about regret, class struggle, or love often come toe to toe in wild humour, like conversing with a sarcastic necktie or arguing with your own ancient reptilian brain. These games, like Yakuza, leverage absurd side content to make their extra content feel alive and worthwhile, while steeping the player in a world where even the offbeat detours brim with life and meaning.

Embracing the Ridiculous to Find What’s Real

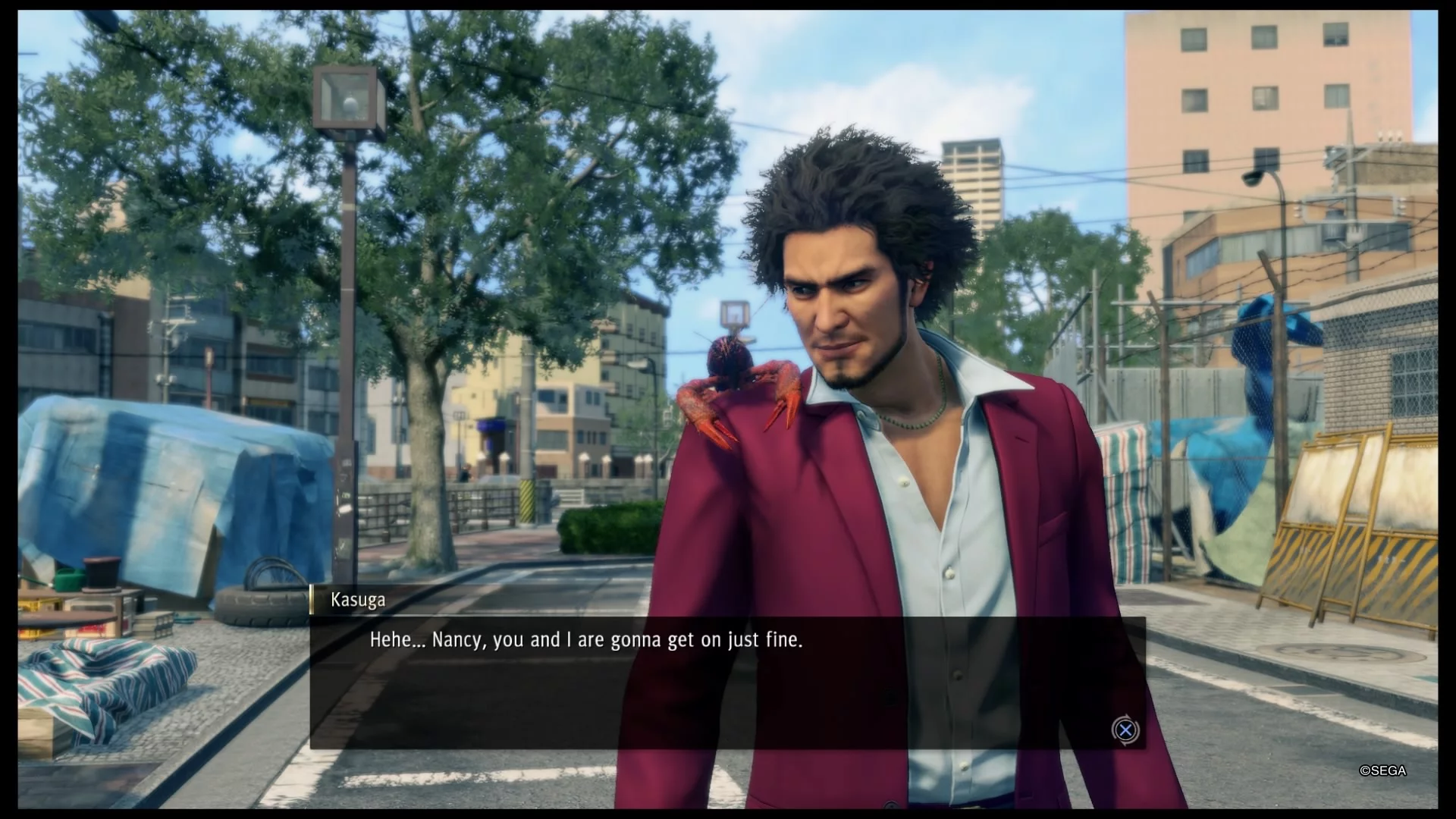

When I reflect on my time with games like the Yakuza series, Iit’s never the main story, or the cutscene melodrama that linger in my mind years later, it’s always those substories, where I laughed and stayed in my mind. I remember in Yakuza: Like a Dragon where Ichiban befriends a crawfish(Nancy!) he saved from becoming dinner; it’s absurd to see an ex-yakuza cradling a pet crawfish, but that absurdity belies a kindness and his innate desire to protect the innocent, however small. It strikes me that these games are teaching an affect theory lesson in practice, games allow us to rehearse feelings and explore our emotions in a safe, playful environment. Absurd sidequests let us rehearse empathy in scenarios we’d never encounter in reality, and gently nudge us to drop our cynicism and engage with an open heart, to see the vulnerable core inside every oddball. In doing so, they give new texture to how we relate to people in our own life, and maybe we become a bit more likely to chuckle instead of scowl at life’s little absurdities, and a bit more willing to extend kindness to strangers with their own struggles.

Ultimately, the grotesque humour and heartfelt sincerity of these side stories are two sides of the same coin. Humour is not the opposite of seriousness; it’s a different route to the same destination. A route that catches us unaware, leading us through the back alleys of emotion instead of the main road. On that path, we often find more honest reflections of human vulnerability than on the straight highway, and there’s a truth that only absurdity can convey; how people really are when the armour of daily life falls off. As I wandered through Kamurocho, every absurd encounter became a tiny illumination: the overly dramatic pocket-circuit racer revealed the genuine childlike passion that even adults carry inside; the lady obsessed with her pet crawfish showed how everyone craves connection and purpose, sometimes to bizarre lengths; the roaring patriarch who loved karaoke taught me that even the fieriest of souls need moments of fun. These are emotional truths delivered not through solemn monologues, but through play and laughter.

In a world that can often feel disjointed and absurd in far less charming ways, there’s something really reassuring about this design philosophy, because it suggests that by embracing the ridiculous, we don’t escape reality but rather engage with it even more. The laughter opens a door to empathy that sternness might keep shut, and the grotesque exaggeration makes it safe to confront uncomfortable feelings and come out smiling. As the games remind us, life’s beauty is entangled with its ephemerality and imperfections. Sidequests, in their whimsical, fragmentary narratives, really do celebrate exactly that.

Every single time I play a new Yakuza, I just know I’ll seek out these side stories actively. They’ve taught me to find meaning in the mundane, and to pause the epic quest and listen to NPCs with problems that are funny, trivial, or strange. Because often, there lies the emotional heart of the game. The Yakuza series, our main example, proves beyond doubt that a game can be both emotional and absurd without sacrificing its narrative integrity, and in fact can strengthen it. Absurd sidequests remind us that heroism is sometimes just helping a neighbour or sharing a laugh amid hardship. In their own way, these quests affirm that everybody’s got a little story, and sometimes the silly ones bring us together best. So I embrace the absurd sidequest with open arms, knowing that behind its goofy mask often lies the sincere face of human connection, and that is a treasure worth seeking in any world, real or virtual.