Opening

There’s a specific kind of memory that has been left behind in the school computer lab, and I don’t mean the sharp, crystal-clear kind, but the fuzzy, mouse-clicking, browser-tab-switching kind.

You were supposed to be doing your math work. Instead, you were dragging a line across a white screen, setting it on a nice slope, and hitting the play button. A little dude on a sled dropped in. He wooshed down the track. He hit a wall, then he flew off into empty space. You laughed. You erased the wall. You made a cool loop now, then you hit play again.

No score. No music. No goal. Just a line and a little dude who trusted you with his life.

That was Line Rider, but it could’ve been anything, The The Powder Game, The Sandbox, Draw Play, or even just falling sand from some pixel faucet you left running for no damn reason at all. Flash games were quite literally everywhere. Some were clever, some were actually crazy, most were ugly. But they all had one thing in common: they let you build something without any permission.

There was a time on the internet when you could do that, before apps were platforms. Before AAA games had season passes, and before “content” was a thing you made with the hope that someone might “engage.” There was a time when websites like Newgrounds, Armor Games, and Miniclip were overflowing with free experiences made by strangers, often teens and twenty-somethings, and served up raw. Not polished, nor branded. Just made for fun.

And somehow, even though most of it was broken, it still felt like magic.

Actually, I’d wager because it was broken, it felt like magic. It felt like you could make it too.

This is a story about that feeling. About what it meant to be handed a blank digital space and a few tools and be told, “Go nuts, lil’ person.” No rules, No win state. Just pure play.

That time when the internet let us be creators before it made us “creators™.” And messing about was encouraged, and failure didn’t have a price. When you didn’t need to monetise everything damn thing.

This was the crayon era of the internet, and for those of us who lived through it, even just for a little while, it shaped the way we think about everything creatively. It made us more curious, experimental, and more willing to build things just to see if they worked. And it’s something we’re still grieving, whether we’ve said it out loud or not. Because the internet doesn’t work like that anymore, and it probably never will again.

No Rules, Just Sleds

Flash games didn’t really care if you won. In fact, a lot of them didn’t even have a way to win. There was no finish line, leaderboards, or progression path. You loaded them in a browser window, poked and prodded at them, broke them, maybe refreshed the page if they froze; and that was the whole deal. You weren’t a player in the traditional sense. You were a participant in this system of creation. And often, you were the only one in charge.

Take Line Rider. It quite literally just gives you a pencil and a blank canvas. That’s it. You draw things like slopes, ramps, and falls and then you hit play. The tiny rider follows the gravity and momentum, and that sometimes turns out great, other times with neck-snapping failure. But it never punishes you. It never asks for more of your time. It just, by design, invites you to try again. To tweak a slope just a little. To add a loop de loop. And to give it another go.

Or The Powder Game, the physics sandbox where you drop fire on ice, spawn in stick figure clones, dump water on lava or acid, throw in some wind, and just see what happens. You aren’t really solving a thing. You’re just experimenting, and just playing with the elements. Sometimes it turns into art, and sometimes it just crashes the game. Either way, it’s yours to make how you see fit.

A lot of these weren’t “games” in the traditional sense.

They were toys, tools, kind of micro-worlds. They had more in common with a pile of LEGOs or a box of coloured pencils than they did with hero shooters or mobile apps. They were built on invitation, not instruction. And nobody walked you through what you were supposed to do. The act of exploring was the game itself.

And that was important.

Because in a digital world that is increasingly defined by what it expects from you, Flash games expected nothing. You weren’t improving your rank, or earning irl currency. You weren’t chasing future goals. You were kinda just doing things because you could.

This kind of unstructured play is much more radical than it looks like. It resists efficiency. It resists gamification, and it resists value extraction. You weren’t producing anything of any economic worth. You were actually wasting time, but in the most beautiful, generative, creative sense of the word.

It’s the kind of freedom most adults spend years trying to claw themselves back to, through hobbies, therapy, or a hundred-dollar productivity app that promises to simulate your childlike focus. But for those of us who grew up in the Flash era, we didn’t need a mindfulness coach to tell us how to “engage with play.” We had a mouse, a browser, and a .swf file full of glitchy code. And we figured it out on our own.

This wasn’t play as distraction. This was play as creation. Curiosity. As your own private joy.

And most of all: there weren’t any stakes.

Nobody was watching, or judging. You didn’t even save your work. You just opened a game, made a mess, laughed, and closed the window. And even though that moment vanished the second you hit X, it was a hell of a time. Because for once, you weren’t trying to win.

You were just trying something.

And that’s a rare kind of freedom... online or anywhere.

Learning Through Chaos

You didn’t realize you were learning, and that was the beauty of it.

Nobody opened The Powder Game thinking, “Ah, yes, time to intuit the principles of fluid dynamics!” and Nobody booted up The Impossible Quiz with dreams of mastering abstract logic. You weren’t looking for lessons, you were looking for something to mess around with. Something weird that felt like the internet had left it lying out, still hot from someone else’s brain.

And yet, you learned things anyway. I did at least. A lot of structural things.

I learned about trial and error from clicking through a fuck-ton of wrong answers in The Impossible Quiz, where every question was designed not just to fool you, but to mock the very idea of there being “right answers.” I learned that interfaces can lie to you. I also learned to stop assuming the obvious was correct, and to keep trying and thinking outside the box.

In The Crimson Room, I learned patience and observation. The key you need might be hidden in the pixel-thin edge of the bookshelf. And that sometimes, the only way out is to slow the hell down and pay attention. I couldn’t win because I was trying to be too fast, so I slowed down. And I finally beat it because I stuck around, and resisted the urge to give up.

I learned in Stick RPG that life is a fucking grind, and that my choices have weight, and also that capitalism makes you miserable even when you’re made of fucking lines. That if you work at McJobs and sleep in an apartment, you’ll still feel stuck. It was bleak, yes. But it was fun, and honest. I wasn’t going out of my way to be taught, but somehow the game still said something true.

And then there was my favourite one, Interactive Buddy. A little gray ragdoll in a blank room who existed solely for you to throw things at. I know it doesn’t sound like something you’d learn something from, but somehow, I learned about systems there too. Variables, cause and effect, inputs and consequences, and about how even the simplest simulation responds in complex ways if you poke at it long enough.

This wasn’t a school. It was damn simulation playground. And every time you broke something, you learned how it worked.

Because that’s how systems reveal themselves.

Not when they’re explained to you, but when you try to push them, they push back.

Flash games, by their very design, encouraged this. Not with tutorials, but with vulnerability. They weren’t polished. They were glitchy and homemade and half-broken... and that made them transparent. You could see the code failing. See the self-made physics engine buckle, and the ragdoll freak out. That rawness made the system legible.

Compare that to AAA modern games which teach you how to press the right button, at the right time, with the right cooldown, on the perfect lane. You’re rewarded for compliance, and trained like an asset.

But Flash games didn’t give a damn if you “got it.” They just existed, and you didn’t need to play them if you wanted. It was held together by usually just one mate in his home. And they left the door unlocked and let you walk around the space like you owned it.

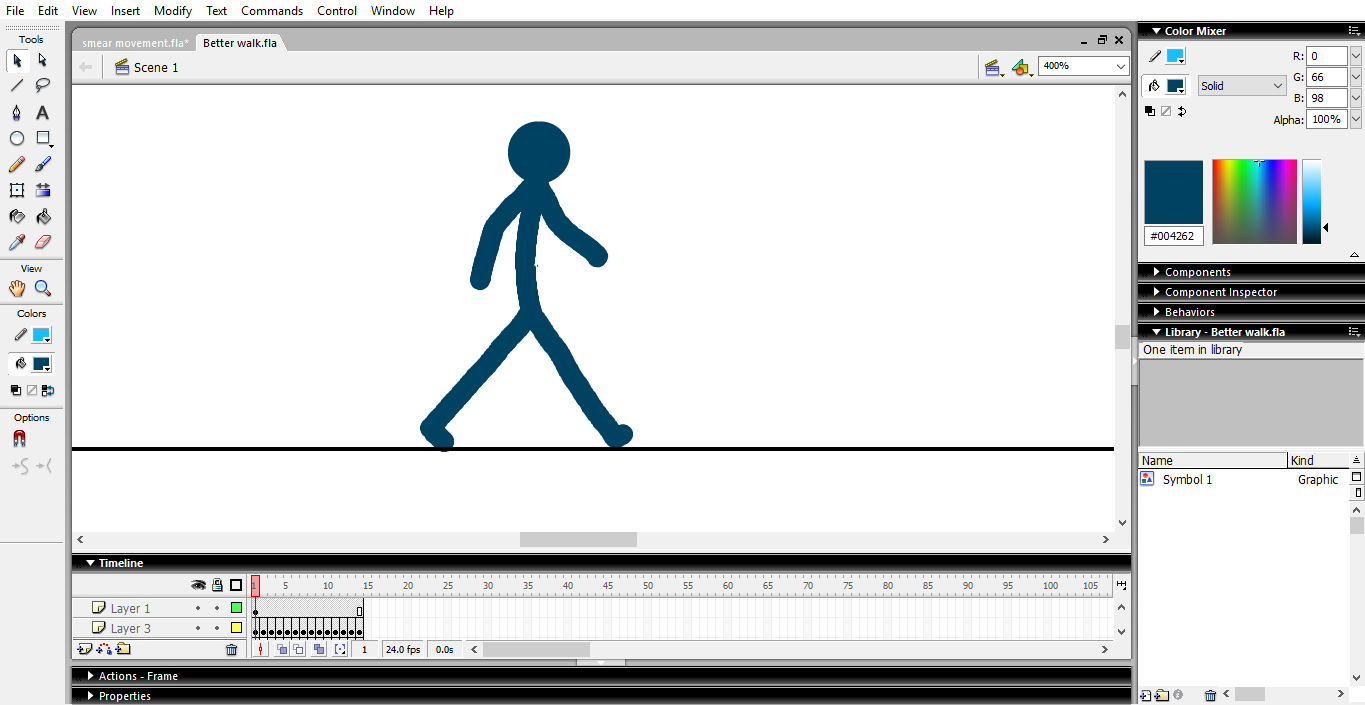

And because of that, I absorbed more than I realised. I learned to test things. If something was annoying me, I’d download the swf file, open up Macromedia Flash, and just debug a few values. I was starting to pay attention to edges and shadows and input lag. To solve puzzles without being told they were puzzles, and to recognise that most problems aren’t linear in nature, and most systems don’t really make sense until you try to break them at least once.

That’s a lesson most people spend their lives learning, and I got it from a stick figure and a busted physics engine at 7.

You didn’t need a gold star to feel it was worth it.

Because there’s something so satisfying about opening up the hood, and figuring it out yourself without a roadmap, or a score.

Just you, a mouse, and a game that wanted nothing but your lovely curiosity.

Add More Stuff (Trust Me)

Some games wanted to teach you the rules. Flash games wanted you to set them on fire.

There’s a distinct kind of chaotic, cursed energy that only existed in the early Flash era, not just in gameplay, but in the way things just refused to behave. A physics engine that barely held together. A menu that jittered along when you clicked it too fast. A ragdoll that launched into orbit if you spawned too many explosives. And that wasn’t a flaw. It was a note that real people, flaws and all, made this thing.

QWOP is the obvious example, and Bennett Foddy is one of the masters of this style.

A sprinting game where each limb had its own button, and none of them worked together. The second you hit “Q,” your runner fucking folded like a puppet with severed strings. You failed damn near instantly. And you laughed at the absurdity of it. Then you tried again. You didn’t get better because the game got easier. You got better by learning how to tap into that chaotic energy, and surf it like a wave.

In Hapland, nothing made sense until you clicked it three times and everything exploded. In Don’t Shit Your Pants, you typed in commands for a man standing next to a toilet... and the only guarantee was that one of them would eventually result in disaster. In Ragdoll Avalanche, you dodged falling spikes with a body that responded like a paper bag full of spaghetti. Everything was batshit crazy, and you could tell kids made it. It was perfect.

Because in that moment, failure wasn’t a punishment... it was a performance.

You’d reload the page just to watch it break again in an even funnier way. You’d show a friend what happened when you clicked the wrong door, and you’d stack too many barrels in Interactive Buddy just to see what frame rate Internet Explorer could survive from. Chaos became a canvas, and destruction was an art style. And the best part? You were the one orchestrating it.

There was no shame in failing because failing wasn’t, and isn’t wrong. It was the point. You weren’t being graded or watched. You weren’t being ranked on some leaderboard next to a stranger with a better PC setup. You were just messing around.

And in that, you learned something almost no other part of life teaches you:

you can break things without breaking yourself.

You could make a mess and laugh at it for ages, or fail instantly and try again. Or explode the simulation you built and rebuild it worse, and nobody would say a word. The world didn’t end when you ruined everything. The game just reloaded, and The Sandbox waited.

That kind of playful failure is powerful. Especially for kids, and even more so online.

Because the modern web, and in particular the modern game, doesn’t make space for that. Everything nowadays is rigid, marketed and tracked. Your mistakes are pre-recorded for all to see, and your performance is ranked. Your behaviour is monetised. And this insipid culture has created a pressure to succeed in front of your friends, or at least make it look like you’re succeeding. And it’s baked into it’s DNA, from top to bottom.

Flash games didn’t care about that life. They said, “Here. Break it.”, “Add more bombs.”, “Uhhh...What happens if you delete gravity?”

It gave you that fucking jank and let you make it worse. It gave you the fire and let you pour oil on it. And the fact that everything barely worked just made it way more fun. It felt human.

That was the secret charm of flash. It reminded you that you were allowed to be unhinged. That things could be a little unstable and still a delightful experience, and that beauty could sometimes live in a busted frame rate and the off-centre sprite that you ended up loving.

And it gave you permission to try things, not because they were smart or strategic, but because they were funny, or weird, or maybe just the spur of a moment thing.

Try finding that in a battle pass.

Zines, Screams, and .swf Dreams

Nobody called them artists, or a scene. And yet, somehow, Flash game creators built one of the richest folk cultures the internet has ever seen.

You have to understand, it wasn’t studios making this shit. I was teens with cracked copies of Macromedia Flash, uploading wild passion projects to Newgrounds. Some were animators learning frame-by-frame, and some were coders experimenting with hitboxes and ragdolls. Some were just kids just making something dumb to make their friends laugh. No publisher, no pipeline, no permission.

And the results? Pure digital punk.

Shit was ugly. Honest. Personal. Brilliant in ways that couldn’t be explained, only felt.

You might not remember the name of the game, but you will remember the mood. The awkward silence before a scream. The poorly cropped background loop. The way a character would just… stop working, mid-animation, as if exhausted by the attempt. The weird menu fonts. The slapdash credits. It wasn’t professional, and that’s what made it special.

This was vernacular digital expression. Not “content.” Not some ai slop. Just people making stuff for each other. Games that weren’t games. Some were experiments, comics in motion, diaries disguised as puzzles or glitch art with interactive buttons.

One Chance was a side-scrolling existential tragedy about the end of the world... and you could only play it once. Loved was a glitchy, minimalist metaphor for identity and abuse. Execution made you choose whether or not to shoot a prisoner, and then never let you undo that. These were made in Flash. And they took five minutes to play. And they hit harder than most shit I see on a daily basis.

This was the internet before virality had become a metric. Before you needed to grow an audience, or optimise your thumbnails, or market your niche for TikTok. Back then, “virality” just meant your friend sent you a link over MSN Messenger that said something like “Mate, you gotta play this, this shit’s so fucked.”

And if you made something, anything... You uploaded it. And people saw it. They maybe left a comment. They maybe shared it. And then you made something else.

It was a gift economy, a world where people made things because they could, and because it felt good. The feedback loop was the joy, not currency. The validation was the existence and presence, not performance. You weren’t pitching to some algorithm, you were throwing sparks into the dark and watching what caught fire.

And it mattered.

Because that kind of creativity- messy, purposeless, unpolished -is where culture thrives. Not in brands, not in trends. Not in launch trailers and social campaigns. But in the sporatic, in the hand-made. In the weird personal thing someone made on a Saturday night and uploaded before going to bed.

Flash games were the zines of the internet. Short, unprofessional, full of feeling, and deeply political without being preachy. Creative not in spite of limitations, but because of them.

And they were everywhere.

You’d stumble across them in forums, in old school computer bookmarks, in half-dead web directories. You didn’t “follow” creators. You discovered them, like buried treasure. Someone had made this. Someone had put this here for you. And even if they didn’t know you’d find it, they’d made it anyway.

There’s something profound about that.

Art is sacred when it isn’t trying to sell you something.

It’s beautiful when the kind of play that asks for, has no reward.

We didn’t recognise it at the time, but this was a cultural movement.

And because it didn’t fit the standard box of “game” or “media” or “art,” it slipped through the cracks. But it was in fact all of those things, and more.

It was creativity without permission, publishing without prestige, meaning made by kids, in browsers, with tools we scrounged around to find.

And it was ours.

The Silent Death of a Beautiful Era

There was little explosion, and sad goodbye posts online when it happened. One day, Flash just… stopped working.

By 2020, browsers had dropped support. Adobe had pulled the plug on it. The little gear-shaped “play” buttons were gone. Thousands... maybe millions, of games, animations, tools, toys, and strange artifacts vanished from daily use. Most were preserved, but some weren’t.

It felt like waking up and realising your childhood bedroom had been bulldozed. Not because you needed it. Just because someone decided it was old.

Technically, this was a “necessary evolution.” The web moved forward. Flash was insecure, clunky and vulnerable. It couldn’t keep up. On the other hand, HTML5 was cleaner, safer, and faster. Developers moved on, and platforms modernised.

But all that technical progress came with cultural amnesia. Because the internet doesn’t remember weirdness unless people are loud, and fight to preserve it. And most of the time, weirdness doesn’t have advocates.

The Crimson Room, the ragdoll torture sims, the surreal platformers with strange physics, they weren’t prioritized. Not by museums. Not by big studios. Not by most users. These weren’t “important” games. They weren’t part of a franchise, and didn’t win awards. They just existed...and then they didn’t.

And the silence around that disappearance says something. It says we still don’t understand how meaningful “unimportant” things can be.

What got preserved were the highlights, the top 10s, viral hits, the stuff people remembered. But the rest? All those one-off games you found by accident in the sidebar? Gone. All those sketchy downloads from pages hosted on someone's college server? Gone. All those weird, heartwarming experiments that lived between the cracks of attention? Gone.

The internet is cruel, and it treats anything without metrics like it has no value.

If it wasn’t shared, it wasn’t real.

If it wasn’t profitable, it wasn’t worth keeping.

But the truth is- I lived in those margins.

I spent countless afternoons in that noise.

I grew up in the middle of that chaos, clicking blindly, making memories, and never thinking to bookmark the page.

Flash's death wasn’t just the end of a file format. It was the quiet erasure of a digital folk history.

It was a mass extinction event for creativity that apparently didn’t matter.

That’s not to say it’s all gone.

Projects like Flashpoint, Internet Archive, and Ruffle have done absolutely heroic work. Thousands of games are playable again, and entire libraries have been rebuilt, curated, and sorted. In some ways, Flash culture has never been more accessible, if you know where to look.

But that entire ecosystem is broken.

There’s no central site anymore. No insane front page filled with new submissions from kids with usernames like “Sk8rWeed666.”

No sense of time, friction or randomness.

And most people won’t go looking for what’s been saved.

Because they don’t know it’s missing.

They’ve already moved on to the more polished, optimised, and monetised internet. The one where every AAA game is a product, action is measured, and every damned creative act is expected to have a goal.

And that’s what we lost.

Not just Flash. Not just the games.

We lost the freedom to make something weird and fragile and pointless... and let it live anyway.

We lost the version of the internet that didn’t care if it made sense.

The one that said, “Here’s a box of matches, go build something or burn it down...or both.”

No one will stop you.

And maybe someone, somewhere, will find it and smile.

You Were a God With a Canvas and Nobody Could Stop You

I wasn’t trying to get better, nor was I chasing an upgrade, unlock, or a win screen.

I was sitting at a computer, at school, home, library- wherever, and I was making something that didn’t matter to anyone but me.

A sled track that I thought looked cool, a digital volcano, maybe a puzzle box with no solution. Some Interactive Buddy debug that I altered to have a Wario face, or a maze made out of lines and loops and ideas that only kind of worked.

I drew, clicked, launched, crashed, and started over. I did it again. I made something dumb, or I made something cool. But, I still made something, period.

That was the point.

There was no audience, no monetisation path. There was no clout to farm. I wasn’t a content creator, or an indie dev. I wasn’t a user, or a player.

I was just some kid with crayons, and for a brief, beautiful moment, the internet let you be a god.

Not some vengeful one, but a curious one. One who laughed when things exploded and grinned when things worked. One who didn’t need a reason, or results.

Flash didn’t make me better at games. It made me better at messing around, at trying stuff, at being curious. Better at making broken things and not caring that they were broken at all.

It genuinely gave me a space where failure wasn’t a stopping point, it was a story.

And success wasn’t a prize, it was a surprise. Where creativity didn’t feel like constant pressure, it felt like play.

And even though most of those moments are gone now, and I can’t find half those games again even if I tried, they did something for me. They wired something into my little brain. That instinct to poke, to tinker, to ask “What if I did this?”... that’s still in there.

And now the web doesn’t really work like that. You’re asked to perform well, and to optimise everthing, so it delivers value. The tools my be more powerful, but the freedom is more limited. The playground has a subscription fee, and the crayons come with patch notes.

But if you were there... even just once, you remember.

Drawing a loop in Line Rider and watching your little guy fall off the edge, or clicking the wrong answer in The Impossible Quiz and seeing a bomb go off in your head and in game, or even making a mess in The Powder Game and zooming out and looking at it like it was a tiny universe you accidentally created.

And you remember what it felt like to make something that didn’t matter at all. Which, weirdly, made it matter even more.

You were just there, in the moment, creating something dumb and delightful and fleeting.

And that, somehow, felt more like art than anything you’ve seen with a logo on it since.

So no, maybe it’s not coming back. Maybe the web is too different now, and maybe Flash is gone for good. But that feeling of creative expression no matter how dumb and wild it is? It’s still somewhere in you.

And one day, maybe, you’ll pick up something again- maybe a pen, a tool, a mouse -and you’ll start making something that doesn’t need to be seen, or sold, or perfect.

Something that feels like crayons on a blank screen, feels like joy, and possibility. Like falling off the track, laughing, and drawing a new one.

Just because you can.