Difficulty isn't Everything (Redo)

Read this first.

I wrote this essay to open a conversation, not to settle one. If you come here already certain of the answer, you will miss the point. I am a fan of hard games. I also live with ADHD, autism, and chronic fatigue. When I write about accessibility and difficulty, I speak from experience and from the design questions I just want people to think. It’s my fault for using “Easy Mode” as the pivotal focus, I also was unsatisfied with the original because I wrote it at a stressful time of the year for me.

Do not quote one sentence and build a straw man from it. Do not assume I am reciting someone else’s hot take. If you disagree, respond to the arguments on the page. If you want to engage, do it with evidence and without ad hominem. If you cannot, move on.

Finally, harassment and stalking are real harms; even more so as a black trans woman. Arguing ideas is normal. Targeting people is not, and I will not tolerate it. If you read this and feel the urge to attack rather than discuss, close the tab, touch some grass, and come back when you can explain the disagreement in a sentence. We are here to talk about games and design; keep the conversation about that.

In the past decade, few conversations in games have become as heated or as predictable as the one about difficulty. Soulslike culture has turned “git gud” from a tongue-in-cheek slogan into a kind of belief, and a shorthand for purity in design and authenticity in play. Hard has become synonymous with good, and the idea that a game might offer multiple thresholds of entry was dismissed as indulgence. The issue has moved people into two camps, those who treat friction as the essence of artistry, and those who argue for accessibility as a basic condition of play.

I am not calling to abolish friction or dilute art. This is an argument for plurality. Difficulty options, sliders, and accessibility features do not erase what hard games teach, they preserve the possibility of learning those lessons across a wider range of bodies and minds. What is at stake here is not just convenience, but continuity. The ability for games to remain open, to remain playable, to remain art for more than one imagined audience.

When people talk about that difficulty as the essence of games, what they usually mean is mechanical difficulty, like reflexes, the twitch precision, and hours of repetition that stand between player and victory. But the history of games tells another story. Difficulty has never been a natural law, has always been contingent, and has been shaped by economics, technology, and cultural context. To defend difficulty as a sacred thing, is to ignore the fact that it has always been a constructed threshold, created by human hands, and adjusted whenever circumstances changed.

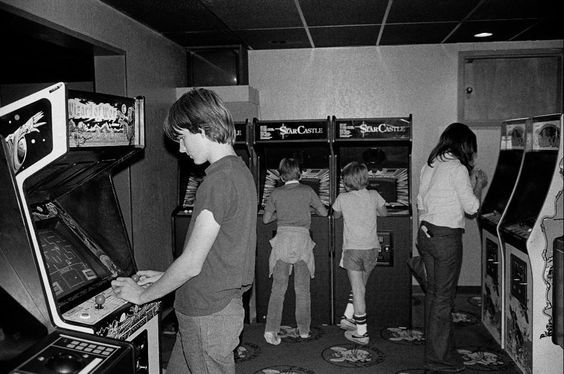

The quickest example I can personally think of, is in the arcade. In the United States, some cabinets were designed to cycle through players quickly, and their difficulty was calibrated to squeeze as many quarters out of a crowd of people as possible. Arcade games did have difficulty settings. Quarter-eaters like Gauntlet or Defender were not simply hard because their designers believed suffering was art, they were hard because it was part of the design, but also because their very business model required it. Players needed to be rotated, and so the difficulty spikes came faster. But they were also social spaces where mastery was cultivated rather than constantly punished. Some other games were designed for longer play sessions, spectatorship, and the habit of tip-sharing between friends crowded around a machine. To paint arcade design with a single brush is to miss the fact that difficulty was not absolute, but changes and bends to the economies in which it existed in.

Consoles also brought their own contingencies. At the beginning, cartridge space was finite, and the production costs were high, so games had to be sold at a price that needed that justification. A short game could be condemned as not worth it, so difficulty in some cases had to become padding, stretching a small game into dozens of hours. Rental markets made this worse. In the United States, some publishers deliberately sabotaged localisations to keep rentals from undercutting sales. What players encountered in that aspect was not pure artistry, but a deliberate obstruction imposed by market logic.

The same patterns also played out on home computers. In the late ’80s and early ’90s, CRPGs routinely withheld vital information, by offering only fragments in manuals or sometimes, not even that. Success sometimes depended on purchasing tip books or dialing into premium-rate phone lines. Here, difficulty was not mastery but opacity, a design that forced players to spend more outside the game itself.

And yet, alongside these stories, there were always counters. Kirby’s Dream Land was intentionally approachable, offering a gentler pace without apology. Doom included its famous “I’m Too Young to Die” setting, inviting those not really in punishment to simply enjoy the ride. EarthBound cut out some of the tedium entirely, letting players instantly win against way weaker enemies rather than forcing it upon you. None of these were accidents, they were deliberate design decisions that showed plurality was possible, and that friction could be tuned without betraying the medium.

Difficulty has never been a single, inviolable essence. It has been a shifting threshold, a negotiation between designers, economies, and audiences. And it continues today. When I hear players say, “that’s just how games are,” I think of these, because games have always been mutable. They have always bent to context, and difficulty is not sacred; it is contingent.

But it would also be dishonest to pretend that hard games offer nothing of value. They give players something undeniable, something I’ve felt myself in the long nights spent against a boss that seemed impossible until suddenly it wasn’t. They teach patience, teaching you to slow down, resist the impulse to rush, and to wait until a pattern reveals itself. They hone skill, the reflexes and timing and precision that only come with practice. They cultivate persistence, not just the willingness to fail, but the capacity to return again and again until you understand. They encourage adaptability, the willingness to experiment with different tools or strategies rather than brute-forcing the same approach. They also demand focus, pulling players into the kind of deep concentration that makes time fall away. They can even teach humility, because failure isn’t a weakness but part of the process.

Beyond the individual, hard games create communities. Strategy guides, tip-sharing forums (Ala the bastion GameFAQs), and speedrunning subcultures have all sprung up around their friction. In those spaces, mastery becomes shared knowledge, and the sense of identity is profound. To be a Souls player, or a no-hit runner, or someone who cleared Sekiro blindfolded, is to claim membership in a culture where endurance and dedication are part of the self. The satisfaction of breaking through, and triumphing over what once felt insurmountable, can be absolutely intoxicating. That shit is real, and it has value.

But the fact that difficulty can teach does not mean it always teaches well. Not every player needs to be pushed through the same wall to learn patience, persistence, or adaptability. Not every lesson requires exhaustion to take root. And the idea that these values only emerge through one calibration of difficulty ignores the fact that friction comes in many forms.

The problem is that difficulty has too often been treated as a binary switch: easy or hard. Change the health numbers, adjust the damage scaling, and call it done. But binary modes rarely capture the nuance of what hard games actually teach. They reduce difficulty to a blunt instrument, when the lessons that the game carries are far more delicate. If patience is the goal, then design systems that cultivate pacing without demanding endless retries. If adaptability is the lesson, then create encounters that reward experimentation instead of punishing every misstep. If persistence is the point, then allow different thresholds for how much persistence a player can sustain before fatigue becomes exclusion.

Too often, difficulty is treated as though it were organic to the game, when in practice it is frequently artificial. Many hard modes rely on blunt numerical adjustments, where enemies simply hit harder, soak more damage, or appear in greater numbers. These changes rarely introduce new ways of thinking or playing. They lengthen encounters without making them deeper, mistaking the endurance for mastery.

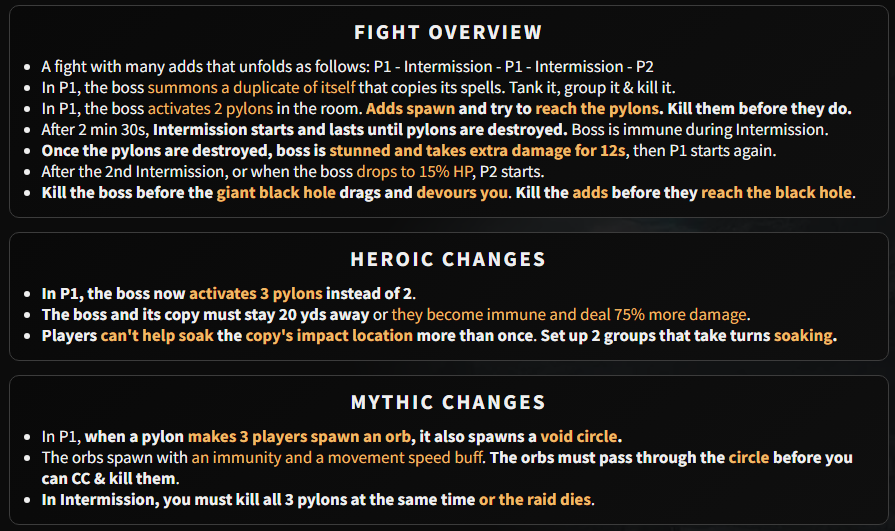

For example, World of Warcraft shows both the weakness of artificial scaling and the potential of designed scaling. Raids are divided into four tiers, where you have Raid Finder, Normal, Heroic, and Mythic. Each step upward includes the expected health and damage inflation, but higher difficulties also add new mechanics, like altered positioning, extra coordination, or entire fight phases that lower tiers never show. These layers can change the kind of encounter it’ll be. Progression isn’t just surviving larger numbers; but learning to manage new demands, and discovering mechanics that force adaptation.

But the game also demonstrates how inflation can become its own endgame. Mythic+ dungeons scale exponentially, with each level increasing enemy health and damage by 10%. Runs are timed, and players must clear a certain percentage of mobs as well as every boss to succeed. At its best, the timer introduces a new form of challenge: efficiency, routing, and group coordination under pressure. At its worst, the exponential scaling creates an arms race where difficulty is reduced to gear checks and number inflation, indistinguishable from Diablo 3’s Greater Rifts. The tension between designed mechanics and artificial scaling is built into the system itself.

Other games show that difficulty need not be about numbers at all. In Dishonored, the true difficulty is stealth, not combat encounters where enemies absorb damage, but the demand for restraint, timing, and patience. The player’s ultimate challenge is expressive, to maintain invisibility, learn patterns, and to resist the temptation of violence when silence is the harder path. This kind of design reminds us that difficulty can be about how we play, not how hard the game hits us back.

The distinction matters. Artificial scaling can pad content, but it does not teach. Designed scaling, by contrast, preserves the satisfaction of mastery while pushing players to learn, adapt, and cooperate in new ways. Expressive difficulty adds another dimension entirely, turning challenge into a question of self-discipline rather than statistics. The prevalence of artificial scaling proves that difficulty is not sacred, that it can be as shallow as it is profound. But examples like World of Warcraft and Dishonored can show us that difficulty can be designed to enrich rather than exhaust, and that the value lies not in suffering itself but in what the game asks us to discover along the way.

It also matters what we mean by “difficulty,” because it is not one thing. There is mechanical difficulty, the reflex-based precision of an action game. There is cognitive difficulty, the mental mapping required to piece together the mysteries of Outer Wilds or The Witness. There is strategic difficulty, the long-term planning of an XCOM or Slay the Spire. There is sensory difficulty, where a game demands rapid parsing of visual or audio cues that not every body can process. There is emotional difficulty, as in horror or grief-centered games that overwhelm through affect rather than mechanics. And there is also social difficulty, the pressure of performing in front of others, and risking humiliation in a fighting game arcade or a competitive lobby.

When we fit all of these into a single word, we can tend to erase the plurality of experiences games actually offer. Difficulty options should not erase that plurality. They should tune one type of difficulty without erasing the others. A lowered damage slider does not make Outer Wilds’ puzzles simpler. A toggle that reduces button mashing does not make horror less frightening. A checkpoint system does not soften the emotional blow of permadeath. Difficulty is already many things, and the artistry lies not in enforcing one threshold but in designing systems that allow different players to learn and to feel across those many registers.

The lessons of hard games are real. I have learnt them myself, and I really do value them. But to insist that every player must suffer equally to be worthy, is to mistake one path for the whole terrain. It is one tool among many, and like any tool, it can be used well or poorly, inclusively or exclusively. The question is not whether difficulty matters, but whether we can design it in ways that preserve its gifts without narrowing who gets to receive them.

For me, difficulty is not an abstract question. I live with ADHD, autism, and chronic fatigue, and that means I experience games differently from the standard player, the imagined able-bodied, neurotypical subject that many designers build around. Repetition, which some people frame as discipline, does not train me. It traps me. ADHD can turn the constant grind into a black hole where hours will just... disappear, not because I’m in flow, but of compulsion. Chronic fatigue means I do not have endless retries to burn; I will eventually run out of energy from the cognitive exertion. I can finish it, yes, but the way there will be painful because of my conditions, not the game itself. Sometimes the difference between an accessible option and none at all is the difference between playing a game and being shut out entirely. These are not questions of patience or preference. They are questions of capacity, and they shape what play can mean for me.

But I am not every disabled or neurodivergent player. Some people with ADHD find repetition soothing, a rhythm that calms rather than exhausts, and some bodies can go longer, others fewer. The point is not that one experience invalidates another, but that no single calibration of difficulty can possibly account for this range. To design for “the average player” is to design for a fiction. Real players are diverse, and their capacities shift not only across individuals but across days, moods, and life stages.

That last point matters more than many want to admit, because aging changes all of us. Reflexes slow, joints ache, and our eyesight starts to blur. The game you loved at 20 may become unplayable at 60 if difficulty is treated as an untouchable constant. Options are not only about disability in the present, but are about continuity across time, and ensuring that art remains accessible to our future selves. Difficulty without options is not just exclusionary now; it is self-defeating in the long run.

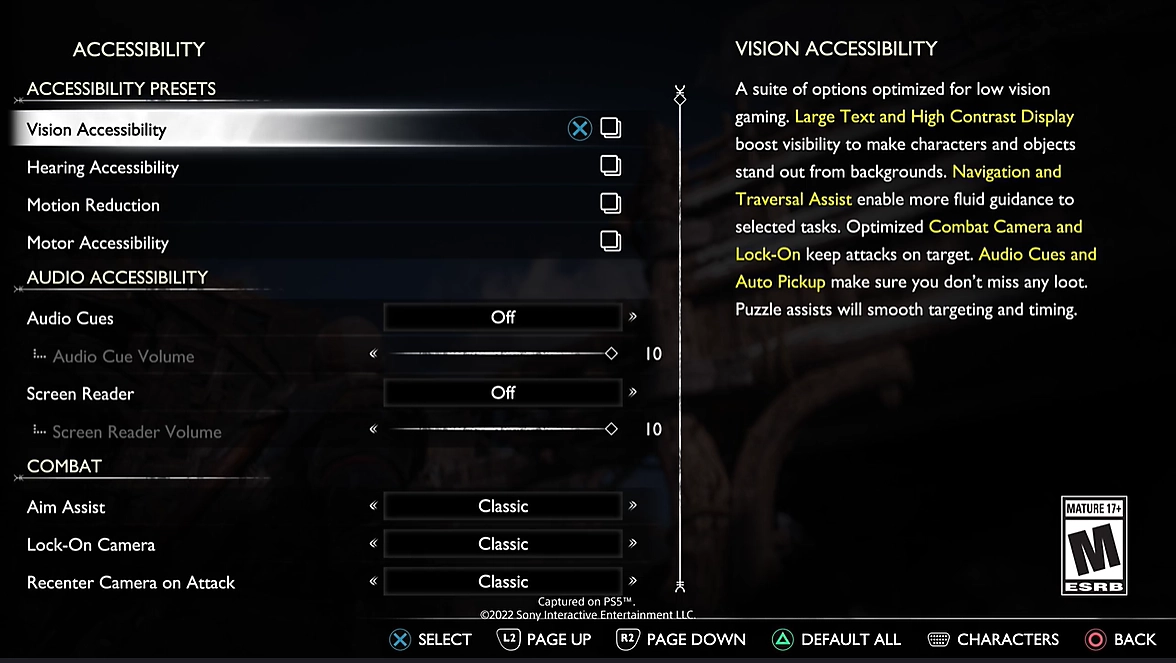

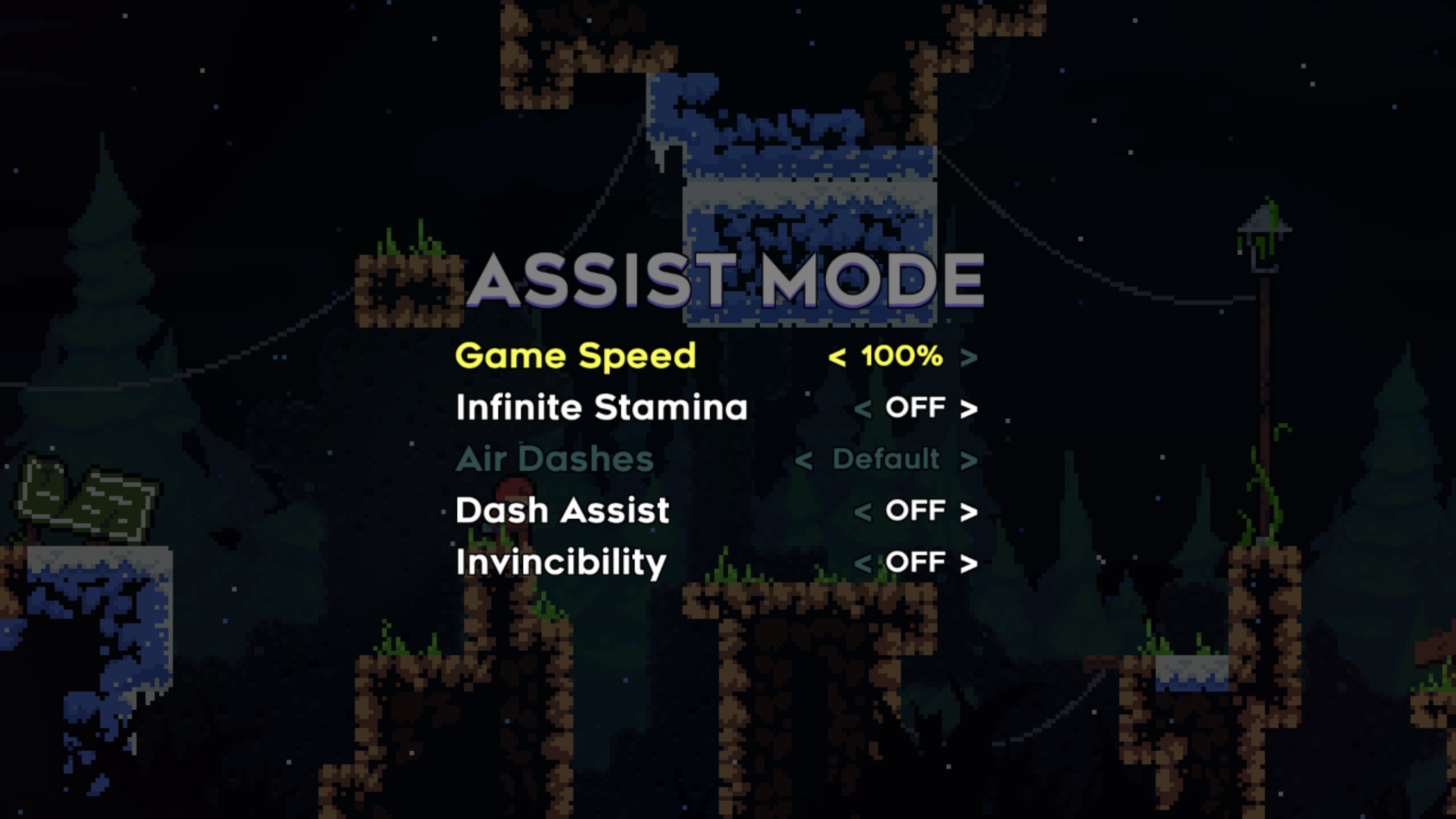

A lot of games already know this. The Last of Us Part II came out with over 60 accessibility features, many of which were praised by abled players for their quality-of-life improvements. God of War Ragnarok expanded that number further, offering 70+ ways to tune the experience. Another Crab’s Treasure approached the problem through sliders, letting players adjust difficulty across multiple dimensions rather than picking a single mode. These aren’t gimmicks, they are proof that accessibility can be treated as craft, and that inclusivity can itself be a form of design elegance. The curb-cut effect, shows just this: just as ramps designed for wheelchair access also help parents with strollers or travelers with luggage, accessibility features in games often benefit everyone.

And I know some people will say that players are not “owed” difficulty options, as though accessibility were a matter of entitlement. But no one frames subtitles as indulgence, or wheelchair ramps as luxury. Accessibility is dignity. It does not remove the stairs or silence the sound. It ensures that the art remains open, and that people who would otherwise be excluded can take part. Some others say that accessibility advocates misuse the language of justice, that asking for options is not the same as fighting structural oppression, but this is a false distinction. When disabled players like myself are told that the art of their time is not for them, that exclusion is not metaphorical, it is real, material, and lived. To dismiss their voices as misuse of language is to erase them entirely.

The truth is that more difficulty options is not simply about making things easier. They come in many forms, like binary modes for quick calibration, sliders that let players change health or damage, assists that toggle specific mechanics like stamina or timing, contextual systems that adjust difficulty invisibly, accessibility features like remapping or hold-to-toggle inputs, and narrative modes that let story-focused players prioritize atmosphere over combat. Each of these meets different needs: motor disabilities, sensory impairments, cognitive fatigue, or simply the desire to engage without exhaustion. These are not concessions, they are forms of design sophistication, and they are ways of acknowledging that difficulty is not a single wall but many possible thresholds.

To make space for this plurality is not to dilute the medium, but to strengthen it. The social model of disability tells us that it is not bodies that disable, but environments that fail to adapt. Games designed around a single imagined player, which is always abled, neurotypical, and young; create environments that disable by default. Games designed with options refuse that fiction, because they recognize that no body or mind is universal, and that art is greatest when it remains open.

The belief that art should be for everyone isn’t new, and it isn’t neutral; it has always been political. For centuries, elites have tried to keep art locked behind money, property, and pedigree. From aristocrats commissioning oil portraits no one else would see, to patrons in Renaissance Europe funding cathedrals where access was mediated by the church, to Cold War governments using modernist galleries as soft power, art has been hoarded and weaponized. When people claim today that games should not “owe” anyone options, they repeat that same history, that the idea that culture is purer when only the right people can touch it.

But there has always been resistance against that idea. Keith Haring scrawled his now-iconic chalk drawings on New York subway walls not because he couldn’t get gallery space, he already had it, but because he refused to let art be confined to those who could afford admission. “Art is for everybody,” he said, and he meant it. Diego Rivera painted sprawling murals across Mexico City, bringing complex histories of labour and revolution to the very people whose lives they depicted. These works weren’t diluted by being public, they were strengthened by it.

Museums have slowly, and quite imperfectly, taken the same lesson. The Prado in Madrid has recreated masterpieces with tactile surfaces so blind visitors can feel the curves and contours of paintings by Velázquez and Goya. The Smithsonian publishes entire guidelines on accessible exhibition design, insisting that disabled visitors are not “special cases” but part of the public the institution exists to serve. Galleries around the world offer braille guides, captioned tours, quiet sensory hours, and even telepresence robots for those who can’t physically attend. None of these measures erased the art. What they erased was the barrier.

Other mediums show the same. Literature has always relied on translation, annotation, and commentary to reach wider audiences. Public libraries, one of the greatest socialist inventions of the modern era, broke the monopoly of book ownership and insisted that knowledge should not be a private luxury. Film was once silent with intertitles, then subtitled, dubbed, captioned, and audio-described. Opera companies now project surtitles (and now even braille) above the stage.

What all of these prove is that accessibility is not an afterthought, not charity, not optional; it is the very condition by which art survives as art. If it is hoarded, it becomes a commodity. If it is shared, it becomes culture. Accessibility does not kill difficulty, or strip art of its challenge; it ensures the challenge can be met by more than the narrow band of bodies and minds that the default design imagined.

Games need to learn this lesson. When players say that difficulty options or sliders would “ruin the experience,” they mistake the lack of one for sanctity. A Souls game does not lose its identity because someone plays it with assist mods, just as a mural does not stop being art because it is on a wall instead of a museum. The unassisted version still exists, still plays just as well and sharpens patience, but it no longer monopolizes the right to call itself “the real game.” To make options is to democratize culture, to treat games not as fortresses to be defended but as bridges to be crossed.

If the history of difficulty options shows us that it has always been contingent, and if lived experience shows us that no single threshold can fit everyone, then the future of difficulty must lie in plurality. Not one mode, but a spectrum of options that preserve the challenge without enforcing exclusion. This is not a retreat from artistry, but a redefinition of what artistry in games can mean.

The framework of flow, can help us see why. Flow emerges when challenge and skill are in balance, if it’s too easy, we fall into boredom; too hard, and we start to freak out. But what produces flow for one player produces fatigue for another. Easy for me may be impossible for you, and hard for you may be trivial for me. Flow is personal, and so any system that enforces a single balance will always exclude. The artistry is not in insisting on one thing, but in designing systems that allow players to find their own balance, and to remain in flow without being driven out of the game entirely.

This stuff is not a radical idea; players have always shaped their own experiences. Cheat codes, Game Genies, and mods were once the ways we shaped the difficulty to fit our lives. Assist features and difficulty options simply formalize a practice that has existed for decades.

For designers, the task is not to flatten difficulty into a binary, but to imagine it as a palette. Sliders, assists, and checkpoints are tools for calibration, not erasure. A well-crafted mode does not remove the challenge; it redistributes it, allowing players to engage with the same systems at different intensities. A toggle that slows combat timing, a slider that adjusts enemy aggression, or an option to add mid-boss checkpoints does not eliminate the lessons of patience, persistence, or adaptability; it allows more players to reach them. Accessibility here is not a burden but a craft, a demonstration that difficulty itself can be designed with the same care as level layouts or combat systems.

Even economics shows how porous difficulty has always been. Free-to-play and mobile games thrive not on challenge but on removing friction, monetizing convenience instead. That model proves that difficulty has never been pure. It has always been shaped by market forces, logic of retention and revenue as much as by the pursuit of artistry.

Of course, there will always be games that make struggle central, that depend on friction as metaphor. Roguelikes that treat failure as part of the story, and masocore games that revel in absurd punishment; these deserve respect as exceptions, and as deliberately specific experiences, but they are not the universal model. Most games do not require exclusion to make their point, and those that do can coexist alongside a broader landscape of accessibility.

The point is that gatekeeping comes in two forms. There is social gatekeeping, the sneer that says you are not a real gamer if you play on easy (which sucks), and there is structural gatekeeping, where the design choices that lock people out of games entirely. The first wounds pride; and the second denies access. The second is far more dangerous, because it is the difference between play as possibility and play as impossibility. Difficulty options, assists, and accessibility features dismantle that structural gatekeeping. They do not make the medium weaker, they ensure it continues.

The future of difficulty is not purity, but continuity. Games will endure not because they guard their gates, but because they remain open, open across bodies, across ages. Plurality does not diminish art; it actually sustains it. The choice is not between hard and easy, between friction and smoothness, but between a medium that narrows itself into a belief and one that embraces the fullness of play, and I think the future worth defending is the latter.

Hard games matter. They teach patience, persistence, adaptability, and humility. But loving them does not mean mistaking them for the standard option. The lessons they teach are not erased by options; they are enriched when more players can reach them through thresholds suited to their own bodies and minds. Without options, games become doors that close. With options, they remain open; not just to the present, but to the future.

The question is not whether games should be hard or easy, but whether they should remain open. History has already given us the answer, this medium survives by changing, adapting, and by making space for more players than the ones imagined at their birth. The future worth defending is one where difficulty is a tool, not a gate. Where the furnace of mastery still burns, but the path to play is never barred.