I still remember the first time I visited that little village of talking animals. It was around 2004, and I was a kid who had just convinced my dad to let me rent Animal Crossing for the Nintendo GameCube from our local Blockbuster. In those days, Blockbuster felt like a magic library of games, and Animal Crossing was a particularly odd find, I’d just been looking at that cover for weeks, deciding if I wanted to waste a week playing a game that I couldn’t figure out from it’s synopsis. I didn’t even have a GameCube memory card at first, which meant I couldn’t save my game. But that didn’t stop me. I would start a new town each time I powered it on, knowing it would all vanish when I turned it off.

I can still picture the layout of my first persistent town, how the river flowed near my house and the bulletin board in the middle of the housing area where villagers would leave me funny notes. I planted fruit trees that actually stayed from one day to the next, and formed friendships with the animal neighbours who finally remembered me from yesterday. There was my boy, Tank, with his working out, and food. They’d notice if I hadn’t visited in a while and sometimes get upset or worried, a detail that made my young heart so happy with responsibility and affection. As a kid with a big imagination (and perhaps a bit of loneliness), having this pocket world filled with gentle animal friends that were happy to see me was profound. It felt genuine and alive. Every day was slow and special: I’d check the mail, maybe dig up a fossil, deliver some furniture item to a neighbour as a favour, and then spend long, idle minutes just fishing in the river or catching bugs. I didn’t have words for it then, but it was peace. I’m absolutely certain it was one of the foundational things that made me like the things I like now. But all in all, it was a kind of simple community that felt both fantastical and intensely real to me, all at once.

Over the next two decades, Animal Crossing has become a steady companion throughout different phases of my life. I moved on from the GameCube original to Wild World on my clunky silver Nintendo DS towards the end of primary school, then City Folk on the Wii during early high school, later New Leaf on the 3DS just before I had graduated, and most recently New Horizons on the Switch as an adult. Each new instalment came into my life like an old friend coming back to town, bringing back that familiar charm but also changing in noticeable ways. Through those years I changed too, I went from a wide-eyed boy to a teen trying to find myself, then transitioning to a (somewhat) responsible adult woman. Funnily enough, as I grew up and the world around me sped up, Animal Crossing was always there, reminding me of the more gentler way of life that I loved. And yet, by the time New Horizons arrived in 2020, I could sense that Animal Crossing itself had been evolving in step with the times, reflecting a world very different from the one I was born into.

I remember in Wild World (the DS version) I had a cranky eagle villager named Apollo who initially acted quite annoyed by me, but after enough conversations and time, he softened up and gave me a nickname. Moments like that felt earned and meaningful, as if I was building real relationships (albeit with cartoon animals). The social bonds were modest, I mean we’re talking about helping a frog neighbour decorate her house or listening to a cranky gorilla’s jokes for the hundredth time, but they felt real. The limits of the game, like the relatively small inventory of dialogue lines or the simple errands, actually made each kind act or funny interaction stand out more. In hindsight, those early designs emphasised slow living: there wasn’t much “gamey” to do except live day by day, pay off your little house loan gradually, send silly little letters, and be a good neighbour. It was so mundane and nice, like the videogame equal of taking a stroll in a small town where everyone knows you by name.

Fast-forward to Animal Crossing: New Horizons on the Switch, and things are a bit different. You arrive on a blank, empty island and basically become its architect and ruler. Sure, the game calls you a Resident Representative, but let’s face it, you’re basically the omniscient town planner, landscaper, and interior designer for the whole island. The power the game gives the player is so immense compared to the older titles. Want to move your neighbours’ houses? Build bridges and inclines at will? Completely change the cliffs and rivers? Go ahead! For the first time, the power to terraform the very earth is in your hands. New Horizons introduced crafting as well, now you gather materials and customise nearly everything, from the pattern on your door wreath to the layout of your island’s fruit orchards. The focus changed heavily to aesthetics and customisation. The game basically just tells you, “Here’s a beautiful blank canvas, go ahead and make your dream town, down to the last square of land.” And boy, did we ever. Within weeks of release, the internet was absolutely flooded with screenshots of players’ stunning island getaways: meticulously themed gardens, zen rock parks, beachfront cafes with perfectly arranged chairs, even in-game replicas of famous world cities. Visiting other people’s islands with the online feature felt like going on Instagram, a tour of carefully curated, envy-inducing personal utopias. My friends and I would spend hours trading rare furniture and complimenting each other’s decor choices. Near-total control was the name of the game.

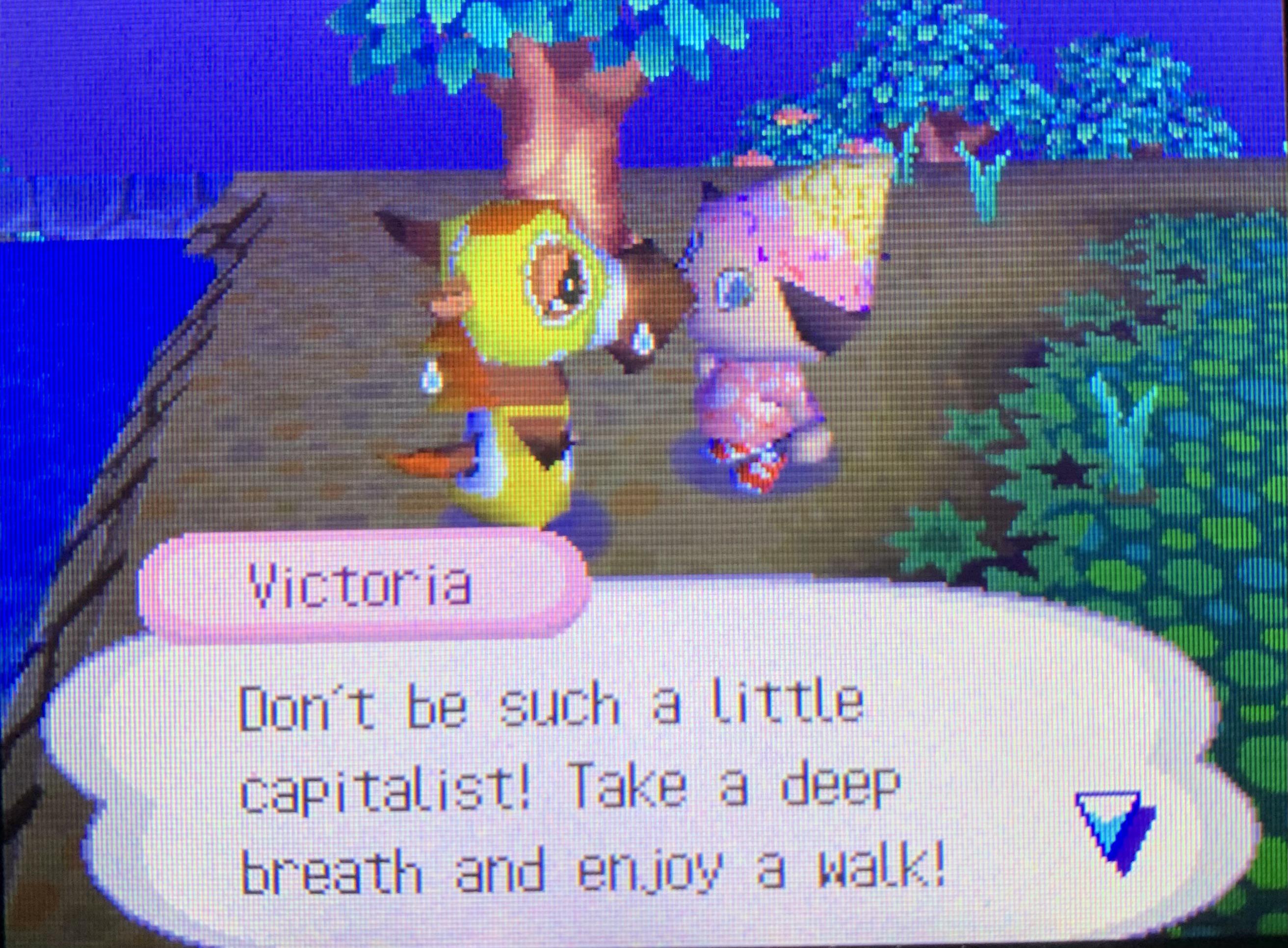

At first, I was in love with this because it was the dollhouse I never had. I spent countless days redesigning my island’s paths and agonising over whether to go with a tropical resort vibe or a small city theme. Every piece of furniture I collected opened up new possibilities for self-expression. It felt wonderful to have so much creative freedom. But over time, a part of me started to miss the simplicity of the old games. In older Animal Crossing titles, I had to adapt to the town; in New Horizons, the town adapts entirely to me. And while it is fun to play omnipotent creator, it also meant that if my island felt soulless or empty, that was kind of my fault. In the Population Growing, if an area of town was barren, well, that’s just how the town generated and I could find the charm in its funny quirks. But in New Horizons, I’d feel an odd pressure that every corner of my island should fit the look, like I was curating my own little paradise to perfection. Most interestingly, the animal villagers themselves took something of a backseat in this newest game. Sure, they’re still cute and enjoyable, but I couldn’t shake the feeling that my relationships with them were much shallower than before. In the original game and its sequel, one of my fondest memories was accidentally upsetting a neighbour and having to work to get back in their good graces. They felt like independent characters with their own lives. In New Horizons, even the most crankiest villagers are unfailingly polite and cheerful, never truly causing conflict. They’ve become part of the island’s scenery in a way, like ornaments to be arranged like furniture, especially since you can now choose where each villager’s house goes, which was something unthinkable in early games. Some longtime fans even joke that Animal Crossing has turned from a community simulator into more of a fashion show or dollhouse, where the core activity is designing outfits and rooms and island layouts, rather than having fun chats and building bonds. When I catch myself spending more time customising the pattern on my character’s phone case than talking to the snooty duck who lives next door, I see their point.

This evolution from a relatively uncontrolled life-in-miniature to a nearly fully customisable sandbox isn’t just some footnote in game design. In many ways, it mirrors changes in our real world and how we view identity and community. The early games forced me to be a neighbour, and to fit into a place and time and deal with a bunch of people I didn’t choose. The latest game lets me effectively curate every single aspect of my environment and even the cast of characters, I mean heck, you can find people talk about throwing away villagers like toys because they’re ugly or don’t fit the aesthetic. It’s as if the series moved from “join this community and find your small place in it” to “build your own perfect community to reflect you”. That change hits on how our sense of self and society has transformed in the era we live in.

When I look at my journey from that first small town to the sprawling island empire of New Horizons, I can’t help but see a reflection of the world’s broader journey during the same period. In the early 2000s when I was that little kid meeting villagers on a small television, the internet and consumer culture were there, sure, but social media hadn’t yet molded how we present ourselves, and neoliberal market logic hadn’t completely saturated every aspect of our lives. I interacted with my in-game neighbours kind of how I interacted with kids on my real-life street, just organically, without branding myself or over-analysing the interaction. Fast-forward to 2025, I, like everyone, have a digital persona, carefully managed feeds, and a sense that identity is something you construct and broadcast. We live under a global neoliberal ethos where selfhood has become a project, and something we actively shape through our consumer choices, lifestyle, and the images we put out into the world. “You are what you buy” or “you are what you post” might as well be the mantra. It’s the age of picking a personal brand, whether you’re an influencer or just some regular person curating your Instagram profile. In New Horizons, I see a cheerful repeat of this idea: your island is essentially your persona. Like, think about it. When you invite others to visit, what exactly are you showing off? It’s not your achievements or your fighting skills, but your sense of style, your creativity, your taste. Are you the kind of person who has a pastel fairyland island? Or a chaotic meme-filled playground? It’s pure self-expression via consumerist means after all, since you’re expressing yourself by how you arrange virtual things (i.e: items, patterns, buildings). In older titles, if a friend visited my town, there wasn’t much I could do to impress them except maybe show off a rare fish I caught or introduce them to my favourite villager. In New Horizons, I found myself almost anxiously preparing my island for visitors like I was hosting a house party. I’m cleaning up weeds, placing cool furniture set pieces, and crafting matching outfits. I started laughing at myself afterwards, like girl, wasn’t this shit supposed to be a relaxing? but it somehow felt important that my island projected the right image. This was curated selfhood in its purest, silliest form.

It feels like we’re living in simulacra, preferring the copies over the originals, and sometimes preferring them. After all, the Animal Crossing version of a cafe (with its K.K. Slider tracks and villagers sipping tea) can absolutely did feel more comforting than any real cafe during a time of constant lockdowns. It’s an aestheticised, controlled version of community life, in other words, a safe simulation of society.

But there’s another side to this coin. While we were busy curating our perfect islands, something else was happening to how we as players behaved, something that ties into that, which is the culture of self-optimisation. It feels like modern society doesn’t need external bosses or disciplinarians as much because we’ve internalised them. We drive ourselves to exhaustion trying to be the best version of ourselves. So we treat life as an endless project of improvement. Disturbingly, I found myself bringing that mindset into Animal Crossing at times. The game that once taught me to chill and enjoy the moment became, if I wasn’t careful, another place for my completionist, perfectionist tendencies. I saw it in how I approached daily play, I had to rush and check the shops every day so I wouldn’t miss a new furniture item. I absolutely had to grind for the rare fish this month because it would be gone next month. I made sticky-note to-do lists of in-game goals, like planting more hyacinths to breed blue flowers, or earn 100,000 Bells to terraform and build the next area. One night I caught myself setting an alarm for 2am to catch an elusive fish (a Barreleye if you’re wondering) that only spawns at night. I, a grown adult, setting a real alarm clock to catch a virtual fish! It was absurd and kind of funny, but also a bit alarming. Why couldn’t I just let myself miss something? And why did my island need to be five-star perfection? The truth was, I was behaving as if Animal Crossing were just another extension of the achievement-driven world. I’d actually turned play into work.

So, I let go. I started just letting things happen when I found the time to, and not living around it. And after a while, I began to rediscover the magic I felt as a kid, that easygoing contentment of existing in a little community without needing to achieve or showcase anything. And you know what? My villagers in the game didn’t care if I had a themed cafe or a perfectly bred hybrid flower garden. They were just happy to see me, even if I showed up after two weeks with bedhead and cockroaches in my virtual house (yes, that happens if you’re away long enough!). There was a lesson there about real life too, in a world that constantly pushes us to curate and polish ourselves for others, sometimes the most authentic moments come when you step off the treadmill and accept the imperfection.

One reason Animal Crossing always connected with me is that it belongs to a genre called iyashikei, which means healing or soothing. This often describes certain anime, manga, or games that have no conflict or competition, only the gentle rhythm of everyday life designed to calm the audience. (I’ve talked about it before.) When I first heard Animal Crossing described as an iyashikei game, it made perfect sense. Think about the elements that make it healing, like the calming music that changes with the hour of the day, the sound of rain pattering when you play on a gloomy afternoon, or the fact that you can just doze off under a tree and absolutely nothing bad will happen to you. Even the goals in the game are calming, like catching some fish, decorating your little space, chatting with a neighbours, and maybe writing a nice letter.

During the pandemic, the iyashikei nature of Animal Crossing: New Horizons truly shone on a global scale. I remember those dark months of 2020, when each morning brought anxious news and the world beyond my room felt unnerving and dangerous. I would wake up, feeling that familiar pit of stress in my stomach, and then make a cup of tea and turn on my Switch. Suddenly, I’d be on a sunny island where the biggest concern was whether the turnip prices were up or if I had enough wood to craft a new chair. The contrast was almost surreal. Tending to my virtual garden and shaking trees for coins had become a sort of self-care for me. And I was far from alone. Friends of mine who had never been the type to play games before were buying Switch consoles just to play Animal Crossing as a way to cope. The game’s popularity exploded precisely because it offered collective healing. People started sharing stories online about how Animal Crossing helped them deal with isolation, how it gave structure to days that would otherwise blur, or how it had become a bonding activity with family they were stuck at home with. I knew a colleague who played every day with her six-year-old daughter, each on their own Switch, visiting each other’s islands. It became their safe little adventure when real-life playgrounds and schools were closed. The game was actually doing something quite radical, it was reminding us how to simply be with ourselves and each other without the usual trappings of productivity or urgency.

The concept of iyashikei also ties into cultural values around nature and nostalgia. One thing that strikes me is how Animal Crossing emphasises nature’s rhythms in a non-exploitative way. Like sure, you can chop some trees and catch fish, but the game also teaches balance. Chop too many trees and you might find your island looking sad and empty, it’s better to plant new ones and create groves of different fruit. Catch every fish in the sea and... well, you can’t, because fish respawn all the time, a reminder that nature goes on. The seasons change slowly and beautifully, like the cherry blossoms blooming for just a week in spring, or snow falling slowly in the winter, and there’s nothing you can do to speed it up or prolong it beyond its time. I often feel a sense of mono no aware (物の哀れ), a Japanese term for the gentle sadness in impermanence, when I experience a season in Animal Crossing. For example, when the autumn leaves drifted to the ground in late November in-game, I felt the wistfulness I feel during the real autumn, knowing it will pass. This attention to the passing moment can be therapeutic, and it taught me to appreciate what’s in front of me, rendered or not, and not always be chasing the next thing immediately. In a capitalist society that urges constant acceleration, taking pleasure in a moment that isn’t profitable or productive, like watching virtual meteor showers with your villagers just because it’s a pretty sight, is a minuscule act of rebellion. It’s saying that I don’t always have to be maximising something. That I can just exist and that’s enough.

I also found it fascinating how Animal Crossing carries a sort of nostalgia for simpler life, which resonates across cultures. In Japan, where the game was born, there’s a yearning for the old rural hometown (furusato), a place where community was intimate and the pace of life was slower. Animal Crossing villages and islands capture that sort of vibe, they’re kinda like the ideal little hometown you never had (or maybe you did, and you miss it). In my case, growing up in suburbs and then living in big cities, I’ve never experienced the idyllic small-town life except through this game’s lens. Yet it felt somehow familiar and comforting, as if I’m tapping into some collective yearning we all have for a more grounded life. When the game introduced elements like brewing coffee at the cafe (New Leaf had the coffee shop, and it returned in New Horizons), it was about the ritual of slowing down to sit with a friend, and chat over a warm drink. Little details like that added up to a powerful counter to the outside world’s hustle.

Now, twenty years on from that first Blockbuster rental, I sit back and ask myself, has Animal Crossing lost something along the way? Have its deeper values of community, simplicity, and presence been hollowed out by an onslaught of customisation, aesthetics, and the pressures of the modern world seeping in? Or does it still hold a potential to remind us of what truly matters? It’s not a question with an easy answer, it lives in the tension I’ve felt throughout my journey with these games.

On one hand, I do sometimes mourn what feels like a certain loss of innocence. The early Animal Crossing games, with all their clunkiness and limitations (like those tiny inventory slots, the awkwardly slow character movement, the fact that you couldn’t even rotate furniture freely in the GameCube version!), kinda forced you into a kind of humble acceptance. You got what you got, and you made the best of it. And in that constraint, there was a kind of authenticity and creativity. Villagers had sharper edges to their personalities, they could be grouchy or blunt, and not just endlessly praising you. The town had rough patches you just couldn’t smooth out. You weren’t in control of much, and so you learned to coexist and find meaning in small interactions. In the real world, community and identity used to be a lot like that too. You were born into a family, a town and culture, and you kinda had to deal with it and find your place. Neoliberalism, with its gospel of individual choice and market solutions, has changed a lot of that. Now we’re told we can (or should) reinvent ourselves, pick our identities like items from a catalogue, move if a place doesn’t suit us, switch jobs, switch friends even, all in search of the perfect fit, and that illusive optimal life. New Horizons, with its island you can mold like clay, sometimes feels like the videogame poster child of that ethos. And indeed, playing it, I occasionally felt a sense of hollowness behind the frenzy of decorating and collecting. I remember after an especially intense week of terraforming my island into a five-star resort (a rating the game gives you based on how well-developed your island is), I put the game down and felt really empty. I had achieved the beautiful island of my dreams, but those dreams had been partly engineered by seeing others’ creations and that subtle pressure to always improve. My villagers still wandered around aimlessly, but I was too busy moving benches and planting hedges to really enjoy time with them. In chasing that aesthetic perfection, I’d lost some of the soul. It hit me then, that a perfect town isn’t necessarily a happy one, for me at least. Just like a perfect Instagram life isn’t necessarily a fulfilled one. That dollhouse was gorgeous, but it was just that, a dollhouse, static and performative, when removed of genuine interaction or spontaneity.

On the other hand, at its core, the series is still about taking things slow, and finding joy in simple acts. That is not the message most capitalist society sends us on a daily basis. The fact that millions of people, myself included, are so drawn to this game and spend hours in it could be seen as a kind of wake up call. We’re choosing that slower life, over the loud, competitive, violent, or materially obsessed narratives that dominate much of popular culture and our economies. In Animal Crossing you can’t win in any conventional sense. You win by enjoying your day and maybe making a friend smile. In a world that often measures everything in terms of productivity, profit, or clear outcomes, Animal Crossing slipping through as a wildly successful product is almost paradoxical. It sold so well not because it promised any mastery or power fantasy (though it gave more creative power than before), but because it promised a taste of a life where enough is enough. Yes, even New Horizons, with all its new features, ultimately still runs on real-time and gently nudges you to take breaks, talk to your neighbours, and appreciate nature. The game may allow you to customise everything, but it doesn’t force you to. That freedom cuts both ways, where you can either turn your island into a shallow consumerist showpiece, or you can turn it into a personal sanctuary of authenticity. Or sometimes both, on alternating days, depending on your mood.

And let’s not forget the streak of creativity and humour the game has unleashed. People have staged elaborate fashion shows, set up in-game museums of their own art, written music that plays on those comical town tune music boxes, all these acts of creation and sharing that aren’t monetised or optimised, they’re just for joy. There’s something so damn cool in taking a mass produced game and using it to make something personal and heartfelt. It’s like tending a little community garden inside a corporate shopping mall, sure it’s an unlikely place to find real connection, but people manage it anyway.

As I end this, I find that the story of Animal Crossing and my story with it can’t be neatly labelled as good or bad with regards to neoliberal culture. It’s both a product of this era and a subtle protest against it, y’know? The evolution from a quaint village to a customizable island does mirror how our idea of self has shifted, from being a member of a community to being the curator of one’s own lifestyle. That shift also carries the pitfalls of isolation, superficiality, and yes, a kind of hollowness if taken too far. But Animal Crossing in the hands of its players, also shows that we haven’t lost our desire for real connection and meaning. We use the tools of customisation to, ironically, recreate community in new forms. We use the freedom given by the game to sometimes relinquish control and simply be.

So, is the new Animal Crossing a hollow dollhouse or a vessel of genuine, slow living? For me, it can be either, and it completely depends on how I approach it. When I play it like an Instagram curator, it just becomes another consumer showcase, which is fun, but ultimately a bit empty. But when I play it like that kid who wandered into a Blockbuster village years ago, with open-ended curiosity and a willingness to let the moments unfold, it becomes almost spiritual in its simplicity. And it’s in those latter times, when I’m catching fireflies at dusk while a gentle in-game breeze rustles the trees, or when a villager surprises me with an out-of-the-blue gift and a goofy letter, that I feel Animal Crossing reconnects me to something real. It tells me that even under the concrete of capitalism’s demands, there’s some soil where simple pleasures and kindness can grow.

Perhaps the most radical thing of all is that Animal Crossing invites us to play. Not to compete, but just to play for its own sake. In this world that often tells us that every single action must have some kind of purpose or profit, choosing purposeless play is a small act of self-care. In those moments of play, I find a fleeting self that isn’t defined by work or consumption, but by presence and imagination. And that feeling, however ephemeral, is very real and precious.

So here’s to two decades of fishing, fossil hunting, and friendly faces, a journey from a tiny village to a big new world, and the ongoing exploration of who we are within it. I, for one, am grateful that this series has grown with me and held up a mirror to society, even when that said reflection is complicated. And every now and then, when the world gets to be a bit too much, you’ll still find me in my little town, gazing up at the stars with my old animal friends that I’ve known longer than most people. In those moments, Animal Crossing really does affirm that maybe, just maybe, we can slow down and find ourselves again, even under the dazzling and dizzying lights of neoliberal modernity.

K.K. Slider says: "Thank you for reading!"

K.K. Slider says: "Thank you for reading!"